Responsible for some of the “most damaging cyber-attacks in history” since 2012, the Shamoon malware wipes compromised hard drives and overwrites key system processes, intending to render infected machines unusable. During a trial period in the network of a global company, Darktrace observed a Shamoon-powered cyber-attack on December 10, 2018 — when several Middle Eastern firms were impacted by a new variant of the malware.

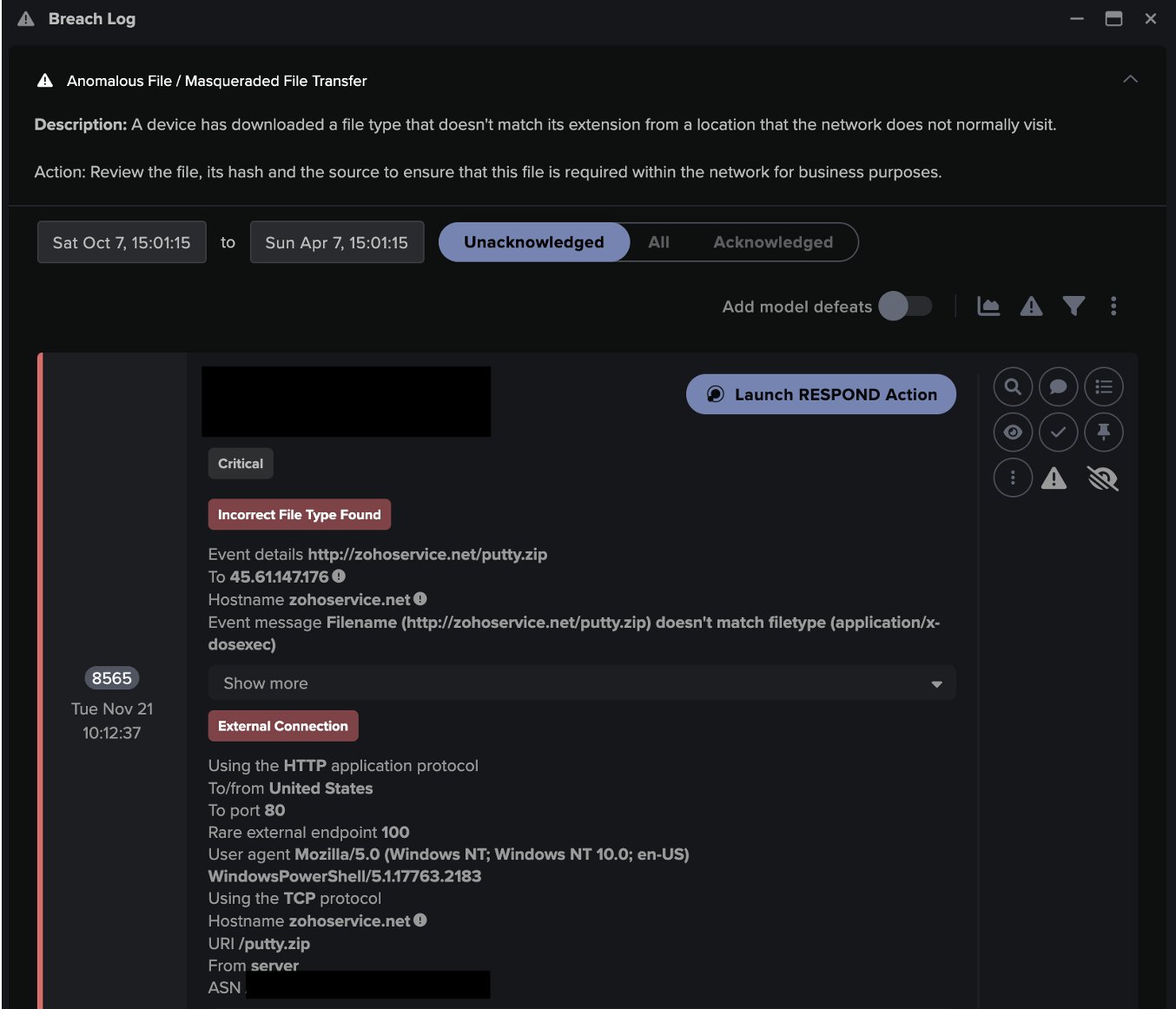

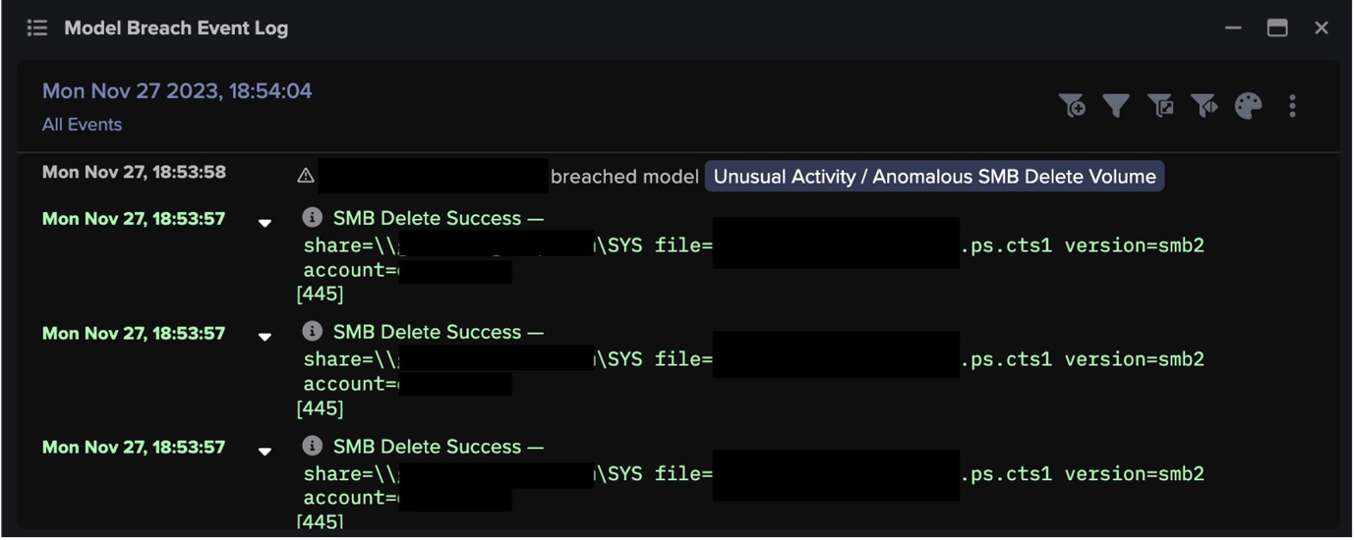

While there has been detailed reporting on the malware files and wiper modules that these latest Shamoon attacks employed, the complete cyber kill chain involved remains poorly understood, while the intrusions that led to the malware’s eventual “detonation” last December has not received nearly as much coverage. As a consequence, this blog post will focus on the insights that Darktrace’s cyber AI generated regarding (a) the activity of the infected devices during the “detonation” and (b) the indicators of compromise that most likely represent lateral movement activity during the weeks prior.

A high-level overview of major events leading up to the detonation on December 10th.

In the following, we will dive into that timeline more deeply in reverse chronological order, going back in time to trace the origins of the attack. Let’s begin with zero hour.

December 10: 42 devices “detonate”

A bird's-eye perspective of how Darktrace identified the alerts in December 2018.

What immediately strikes the analyst’s eye is the fact that a large accumulation of alerts, indicated by the red rectangle above, took place on December 10, followed by complete network silence over the subsequent four days.

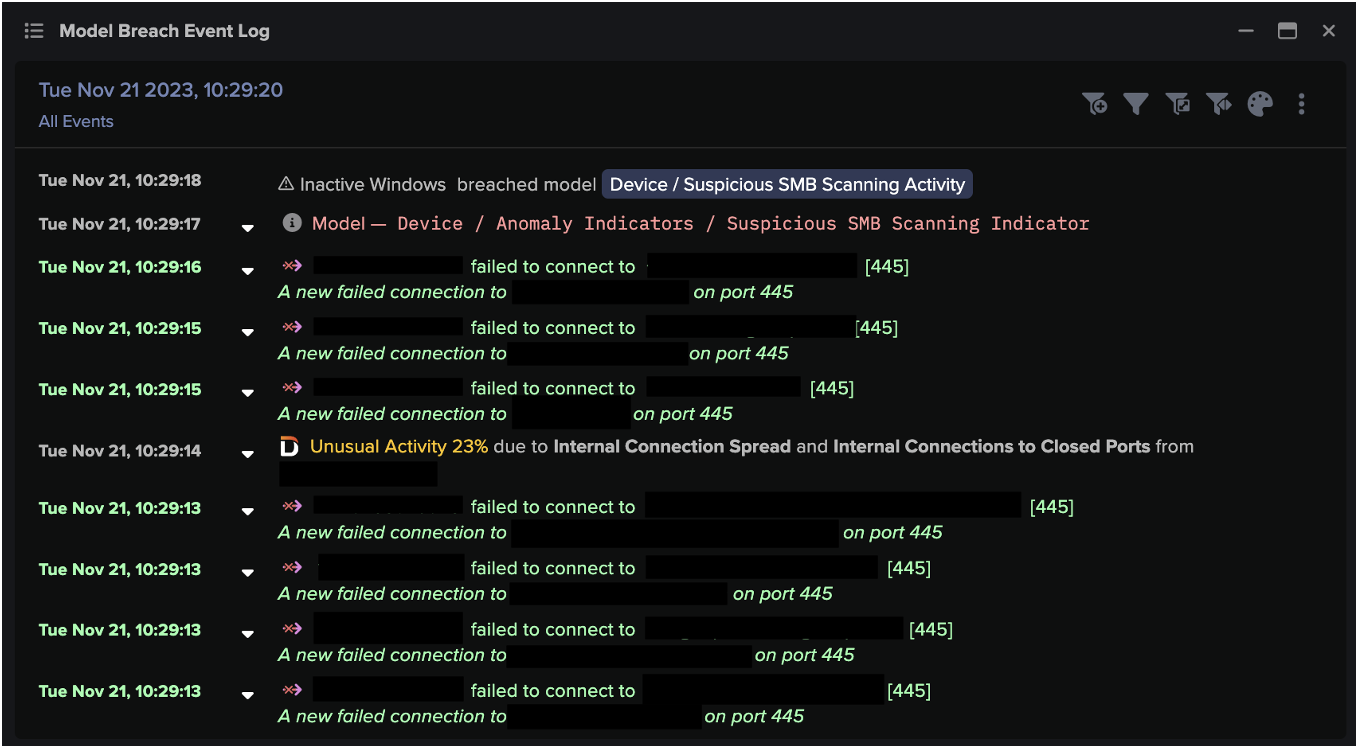

These highlighted alerts represent Darktrace’s detection of unusual network scans on remote port 445 that were conducted by 42 infected devices. These devices proceeded to scan more machines — none of which were among those already infected. Such behavior indicates that the compromised devices started scanning and were wiped independently from each other, instead of conducting worming-style activity during the detonation of the malware. The initial scanning device started its scan at 12:56 p.m. UTC, while the last scanning device started its scan at 2:07 p.m. UTC.

Not only was this activity readily apparent from the bird’s-eye perspective shown above, the detonating devices also created the highest-priority Darktrace alerts over a several day period: “Device / Network Scan” and “Device / Expanded Network Scan”:

Moreover, when investigating “Devices — Overall Score,” the detonating devices rank as the most critical assets for the time period December 8–11:

Darktrace AI generated all of the above alerts because they represented significant anomalies from the normal ‘pattern of life’ that the AI had learned for each user and device on the company’s network. Crucially, none of the alerts were the product of predefined ‘rules and signatures’ — the mechanism that conventional security tools rely on to detect cyber-threats. Rather, the AI revealed the activity because the scans were unusual for the devices given their precise nature and timing, demonstrating the necessity of the such a nuanced approach in catching elusive threats like Shamoon. Of further importance is that the company’s network consists of around 15,000 devices, meaning that a rules-based approach without the ability to prioritize the most serious threats would have drowned out the Shamoon alerts in noise.

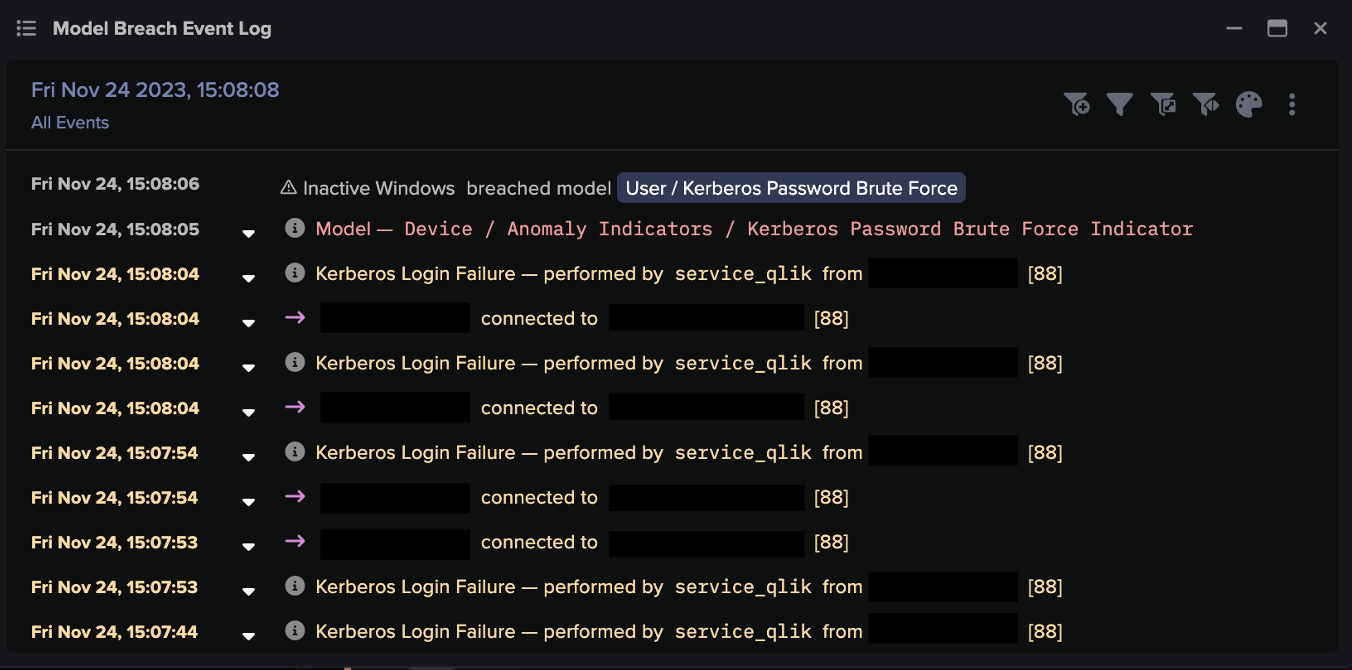

Now that we’ve seen how cyber AI sounded the alarms during the detonation itself, let’s investigate the various indicators of suspicious lateral movement that precipitated the events of December 10. Most of this activity happened in brief bursts, each of which could have been spotted and remediated if Darktrace had been closely monitored.

November 19: Unusual Remote Powershell Usage (WinRM)

One such burst of unusual activity occurred on November 19, when Darktrace detected 14 devices — desktops and servers alike — that all successfully used the WinRM protocol. None of these devices had previously used WinRM, which is also unusual for the organization’s environment as a whole. Conversely, Remote PowerShell is quite often abused in intrusions during lateral movement. The devices involved did not classify as traditional administrative devices, making their use of WinRM even more suspicious.

Note the clustering of the WinRM activity as indicated by the timestamp on the left.

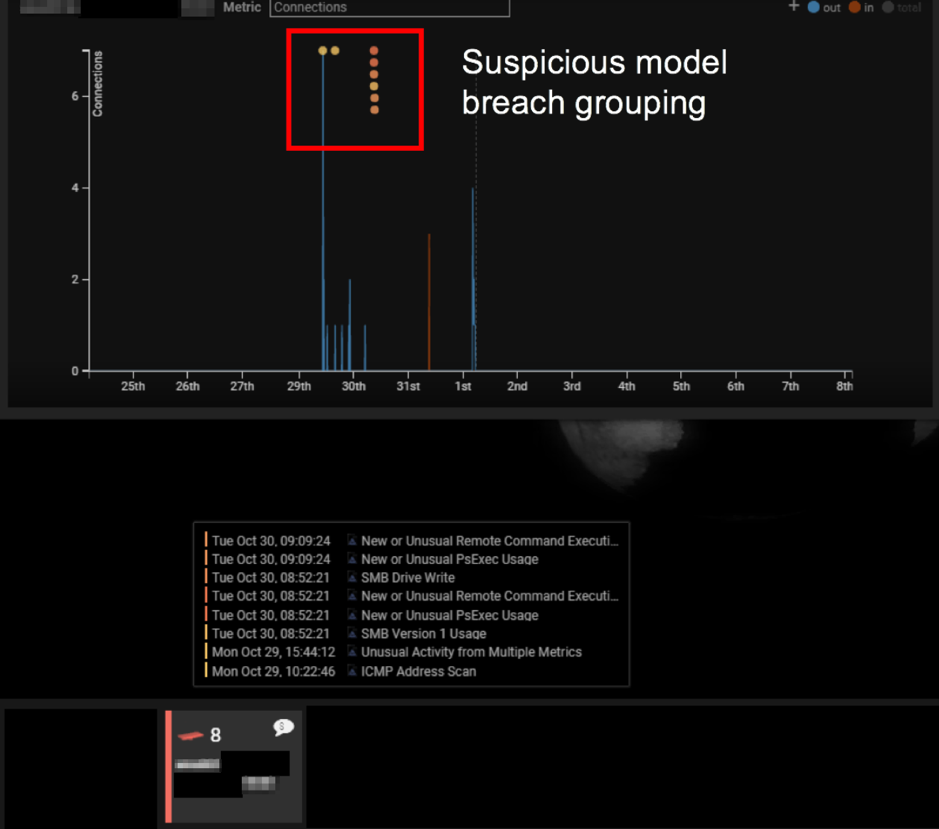

October 29–31: Scanning, Unusual PsExec & RDP Brute Forcing

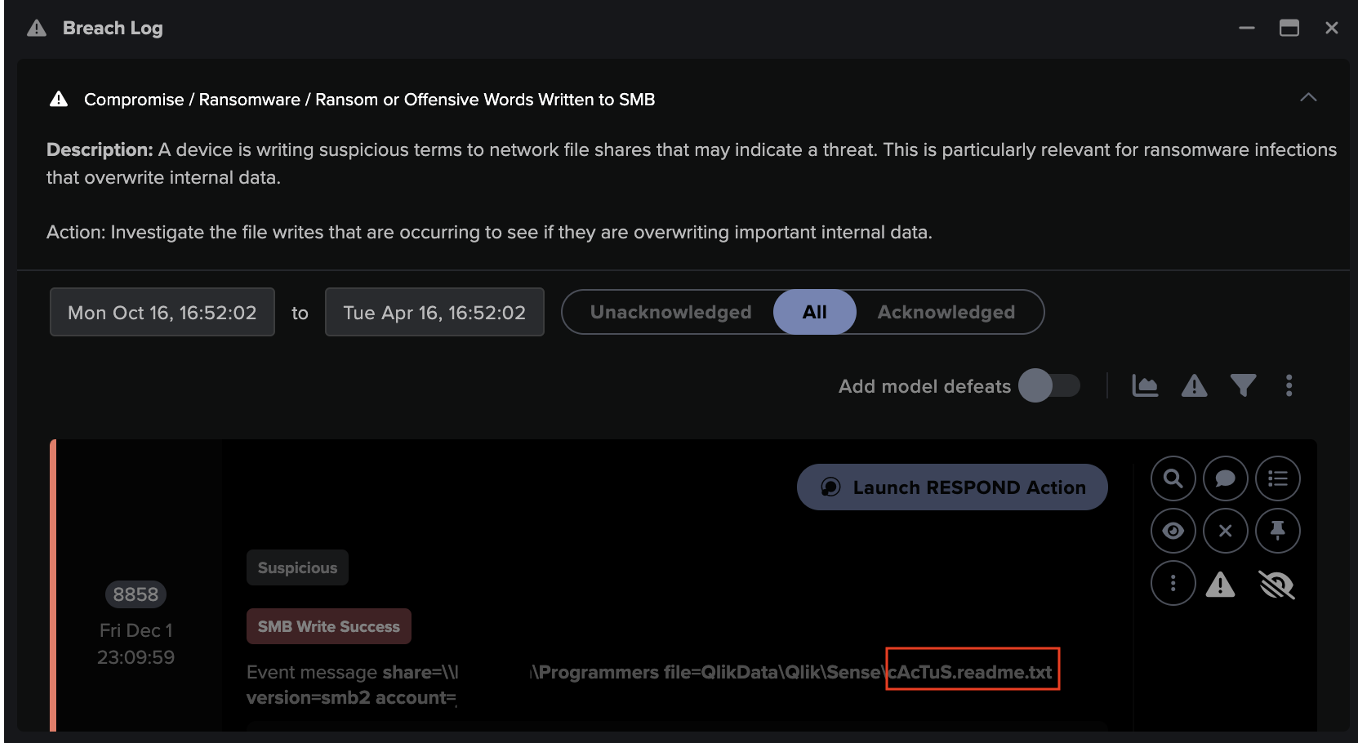

Another burst of likely lateral movement occurred between October 29 and 31, when two servers were seen using PsExec in an unusual fashion. No PsExec activity had been observed in the network before or after these detections, prompting Darktrace to flag the behavior. One of the servers conducted an ICMP Ping sweep shortly before the lateral movement. Not only did both servers start using PsExec on the same day, they also used SMBv1 — which, again, was very unusual for the network.

Most legitimate administrative activity involving PsExec these days uses SMBv2. The graphic below shows several Darktrace alerts on one of the involved servers — take note of the chronology of detections at the bottom of the graphic. This clearly reads like an attacker’s diary: ICMP scan, SMBv1 usage, and unusual PsExec usage, followed by new remote service controls. This server was among the top five highest ranking devices during the analyzed time period and was easy to identify.

Following the PsExec use, the servers also started an anomalous amount of remote services via the srvsvc and svcctl pipes over SMB. They did so by starting services on remote devices with which they usually did not communicate — using SMBv1, of course. Some of the attempted communication failed due to access violation and access permission errors. Both are often seen during malicious lateral movement.

Additional context around the SMBv1 and remote srvsvc pipe activity. Note the access failure.

Thanks to Darktrace’s deep packet inspection, we can see exactly what happened on the application layer. Darktrace highlights any unusual or new activity in italics below the connections — we can easily see that the SMB activity is not only unusual because of SMBv1 being used, but also because this server had never used this type of SMB activity remotely to those particular destinations before. We can also observe remote access to the winreg pipe — likely indicating more lateral movement and persistence mechanisms being established.

The other server conducted some targeted address scanning on the network on October 29, employing typical lateral movement ports 135, 139 and 445:

Another device was observed to conduct RDP brute forcing on October 29 around the same time as the above address scan. The desktop made an unusual amount of RDP connections to another internal server.

A clear plateau in increased internal connections (blue) can be seen. Every colored dot on top represents an RDP brute force detection. This was again a clear-cut detection not drowned in other noise — these were the only RDP brute force detections for a several-month monitoring time window.

October 9–11: Unusual Credential Usage

Darktrace identifies the unusual use of credentials — for instance, if administrative credentials are used on client device on which they are not commonly used. This might indicate lateral movement where service accounts or local admin accounts have been compromised.

Darktrace identified another cluster of activity that is likely representing lateral movement, this time involving unusual credential usage. Between October 9 and 11, Darktrace identified 17 cases of new administrative credentials being used on client devices. While new administrative credentials were being used from time to time on devices as part of normal administrative activity, this strong clustering of unusual admin credential usage was outstanding. Additionally, Darktrace also identified the source of some of the credentials being used as unusual.

Conclusion

Having observed a live Shamoon infection within Darktrace, there are a few key takeaways. While the actual detonation on December 10 was automated, the intrusion that built up to it was most likely manual. The fact that all detonating devices started their malicious activity roughly at the same time — without scanning each other — indicates that the payload went off based on a trigger like a scheduled task. This is in line with other reporting on Shamoon 3.

In the weeks leading up to December 10, there were various significant signs of lateral movement that occurred in disparate bursts — indicating a ‘low-and-slow’ manual intrusion.

The adversaries used classic lateral movement techniques like RDP brute forcing, PsExec, WinRM usage, and the abuse of stolen administrative credentials.

While the organization in question had a robust security posture, an attacker only needs to exploit one vulnerability to bring down an entire system. During the lifecycle of the attack, the Darktrace Enterprise Immune System identified the threatening activity in real time and provided numerous suggested actions that could have prevented the Shamoon attack at various stages. However, human action was not taken, while the organization had yet to activate Antigena, Darktrace’s autonomous response solution, which could have acted in the security team’s stead.

Despite having limited scope during the trial period, the Enterprise Immune System was able to detect the lateral movement and detonation of the payload, which was indicative of the malicious Shamoon virus activity. A junior analyst could have easily identified the activity, as high-severity alerts were consistently generated, and the likely infected devices were at the top of the suspicious devices list.

Darktrace Antigena would have prevented the movement responsible for the spread of the virus, while also sending high-severity alerts to the security team to investigate the activity. Even the scanning on port 445 from the detonating devices would have been shut down, as it presented a significant deviation from the known behavior of all scanning devices, which would have further limited the virus’s spread, and ultimately, spared the company and its devices from attack.

![Cyber AI Analyst Incident Log showing the offending device making over 1,000 connections to the suspicious hostname “zohoservice[.]net” over port 8383, within a specific period.](https://assets-global.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/662971c1cf09890fd46729a1_Screenshot%202024-04-24%20at%201.55.10%20PM.png)