Raccoon Stealer Malware

Since the release of version 2 of Raccoon Stealer in May 2022, Darktrace has observed huge volumes of Raccoon Stealer v2 infections across its client base. The info-stealer, which seeks to obtain and then exfiltrate sensitive data saved on users’ devices, displays a predictable pattern of network activity once it is executed. In this blog post, we will provide details of this pattern of activity, with the goal of helping security teams to recognize network-based signs of Raccoon Stealer v2 infection within their own networks.

What is Raccoon Stealer?

Raccoon Stealer is a classic example of information-stealing malware, which cybercriminals typically use to gain possession of sensitive data saved in users’ browsers and cryptocurrency wallets. In the case of browsers, targeted data typically includes cookies, saved login details, and saved credit card details. In the case of cryptocurrency wallets (henceforth, ‘crypto-wallets’), targeted data typically includes public keys, private keys, and seed phrases [1]. Once sensitive browser and crypto-wallet data is in the hands of cybercriminals, it will likely be used to conduct harmful activities, such as identity theft, cryptocurrency theft, and credit card fraud.

How do you obtain Raccoon Stealer?

Like most info-stealers, Raccoon Stealer is purchasable. The operators of Raccoon Stealer sell Raccoon Stealer samples to their customers (called ‘affiliates’), who then use the info-stealer to gain possession of sensitive data saved on users’ devices. Raccoon Stealer affiliates typically distribute their samples via SEO-promoted websites providing free or cracked software.

Is Raccoon Stealer Still Active?

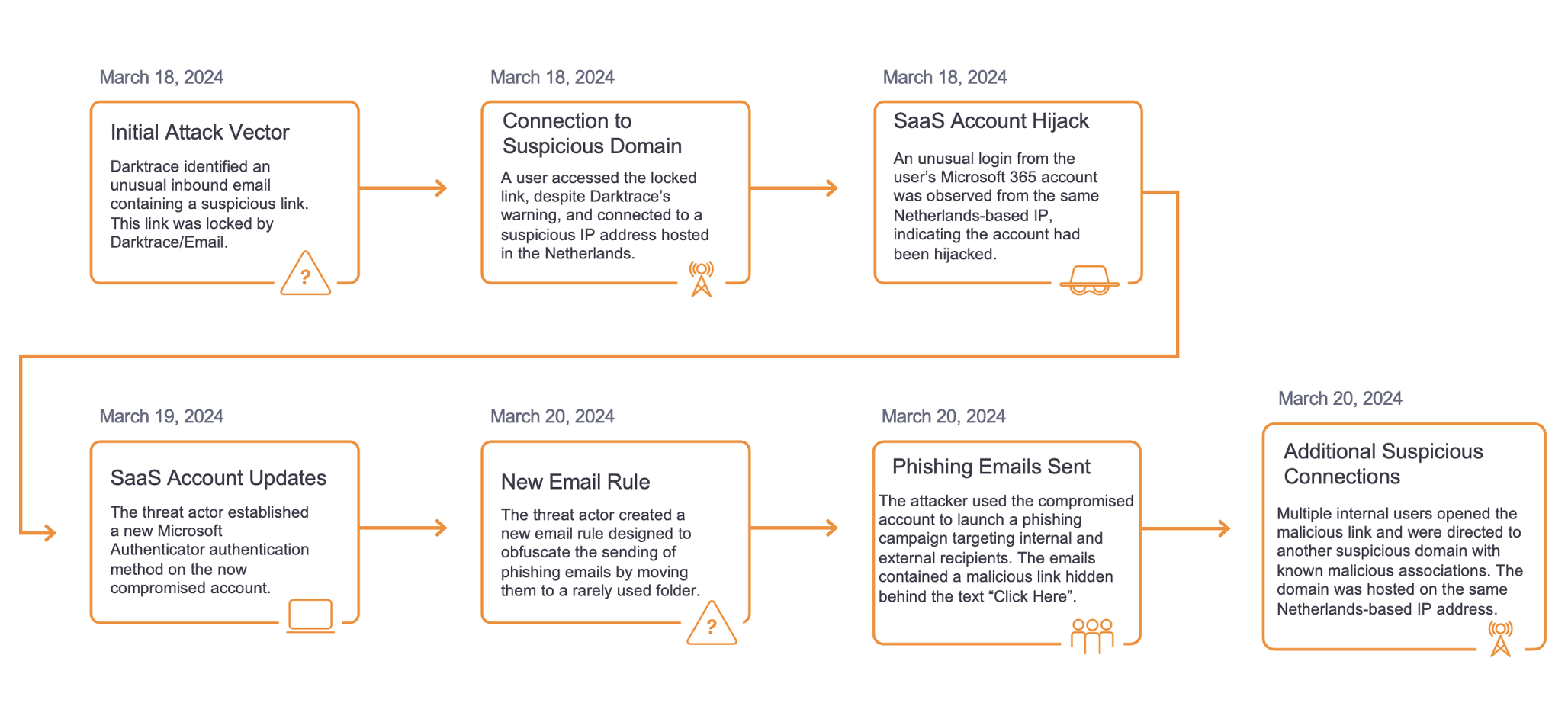

On the 25th of March 2022, the operators of Raccoon Stealer announced that they would be suspending their operations because one of their core developers had been killed during the Russia-Ukraine conflict [2]. The presence of the hardcoded RC4 key ‘edinayarossiya’ (Russian for ‘United Russia’) within observed Raccoon Stealer v2 samples [3] provides potential evidence of the Raccoon Stealer operators’ allegiances.

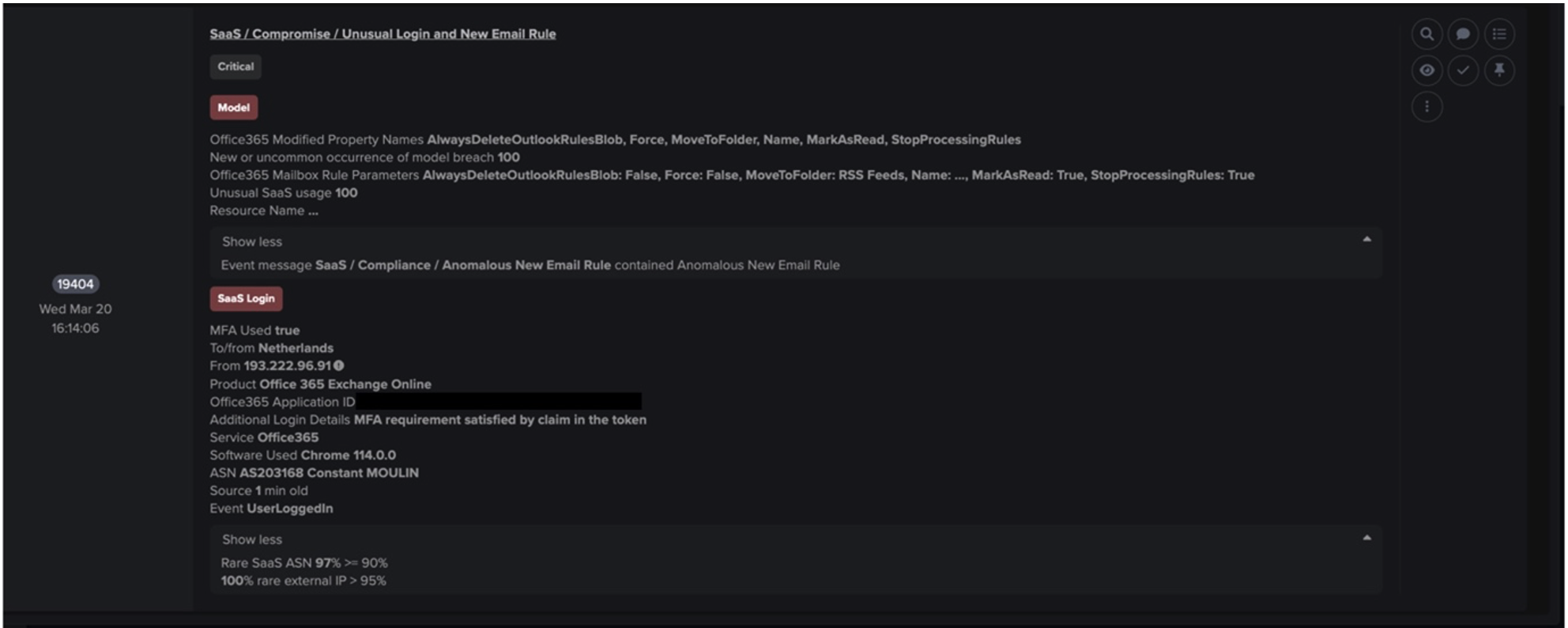

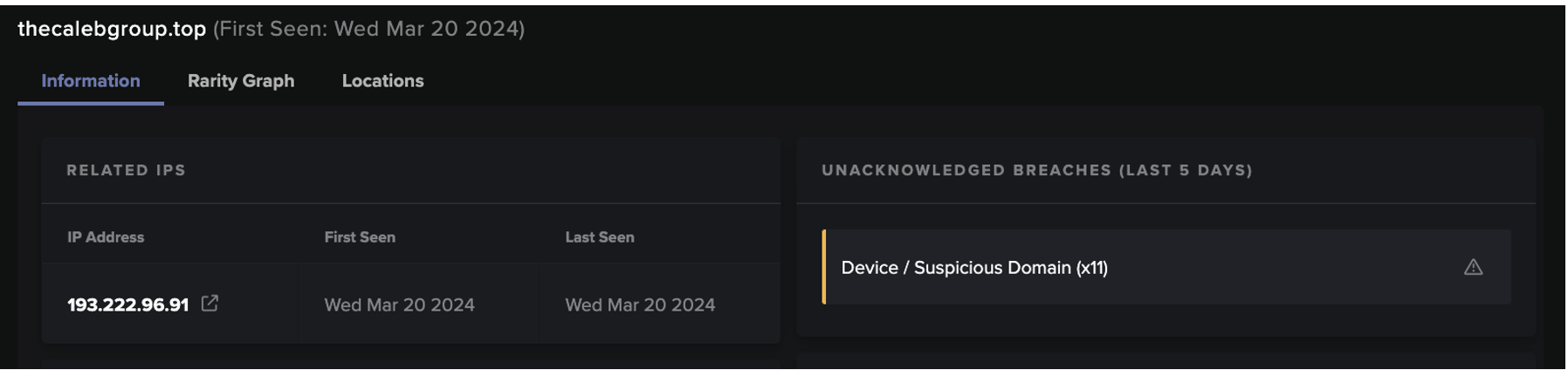

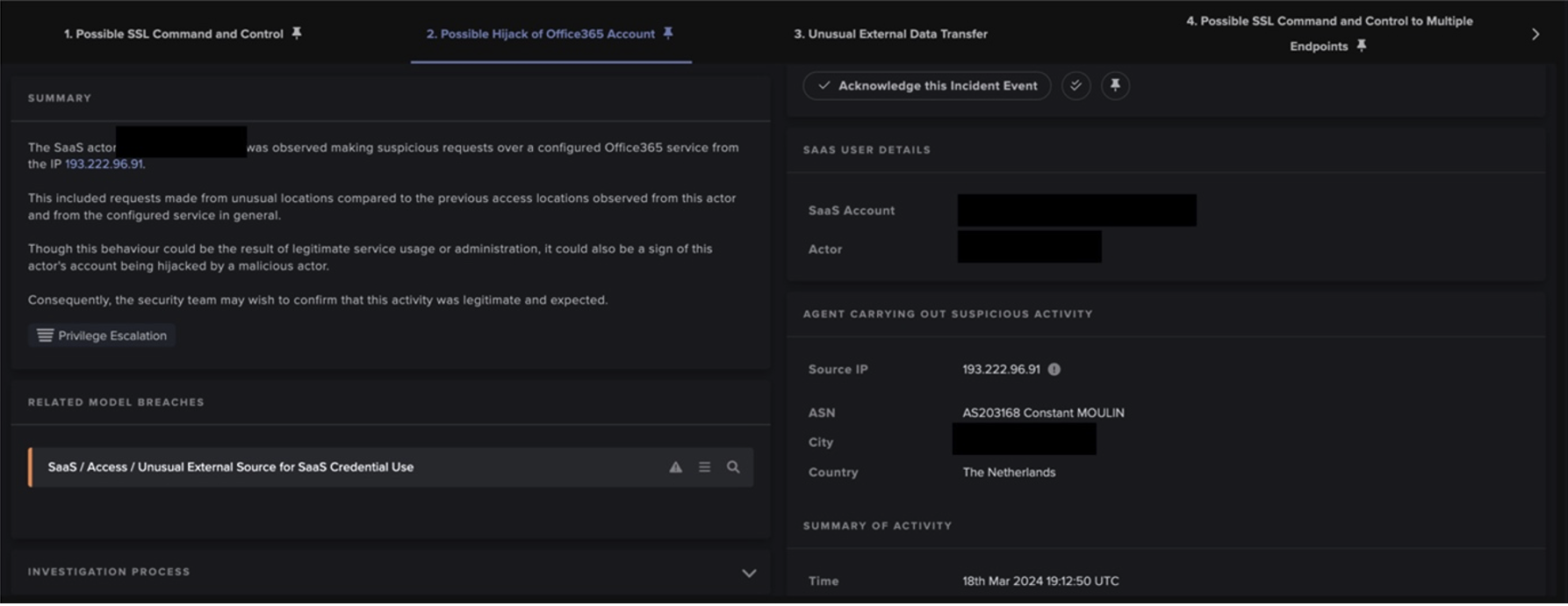

Recent details shared by the US Department of Justice [4]/[5] indicate that it was in fact the arrest, rather than the death, of an operator which led the Raccoon Stealer team to suspend their operations [6]. As a result of the FBI, along with law enforcement partners in Italy and the Netherlands, dismantling Raccoon Stealer infrastructure in March 2022 [4], the Raccoon Stealer team was forced to build a new version of the info-stealer.

On the 17th May 2022, the completion of v2 of the info-stealer was announced on the Raccoon Stealer Telegram channel [7]. Since its release in May 2022, Raccoon Stealer v2 has become extremely popular amongst cybercriminals. The prevalence of Raccoon Stealer v2 in the wider landscape has been reflected in Darktrace’s client base, with hundreds of infections being observed within client networks on a monthly basis.

Since Darktrace’s SOC first saw a Raccoon Stealer v2 infection on the 22nd May 2022, the info-stealer has undergone several subtle changes. However, the info-stealer’s general pattern of network activity has remained essentially unchanged.

How Does Raccoon Stealer v2 Infection Work?

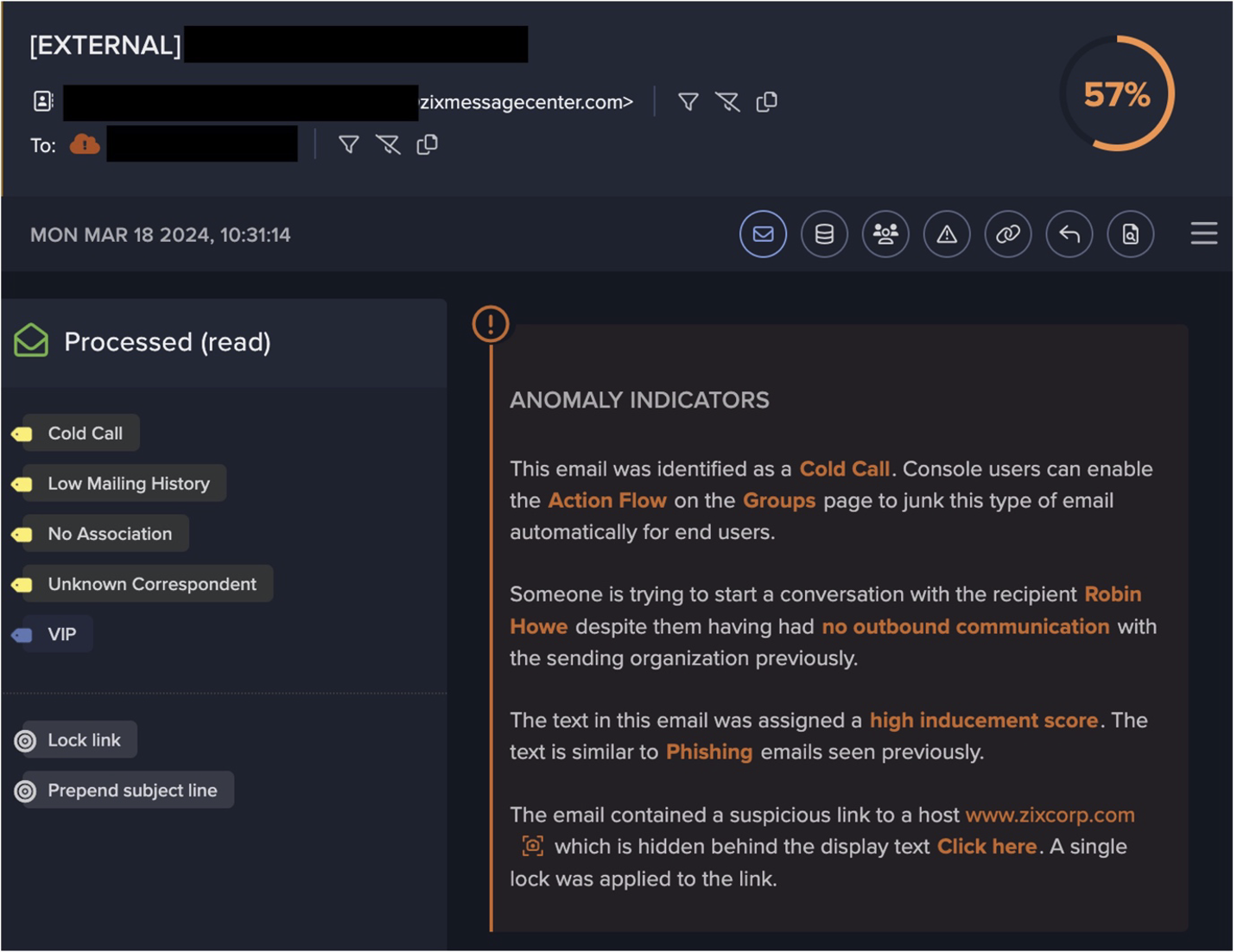

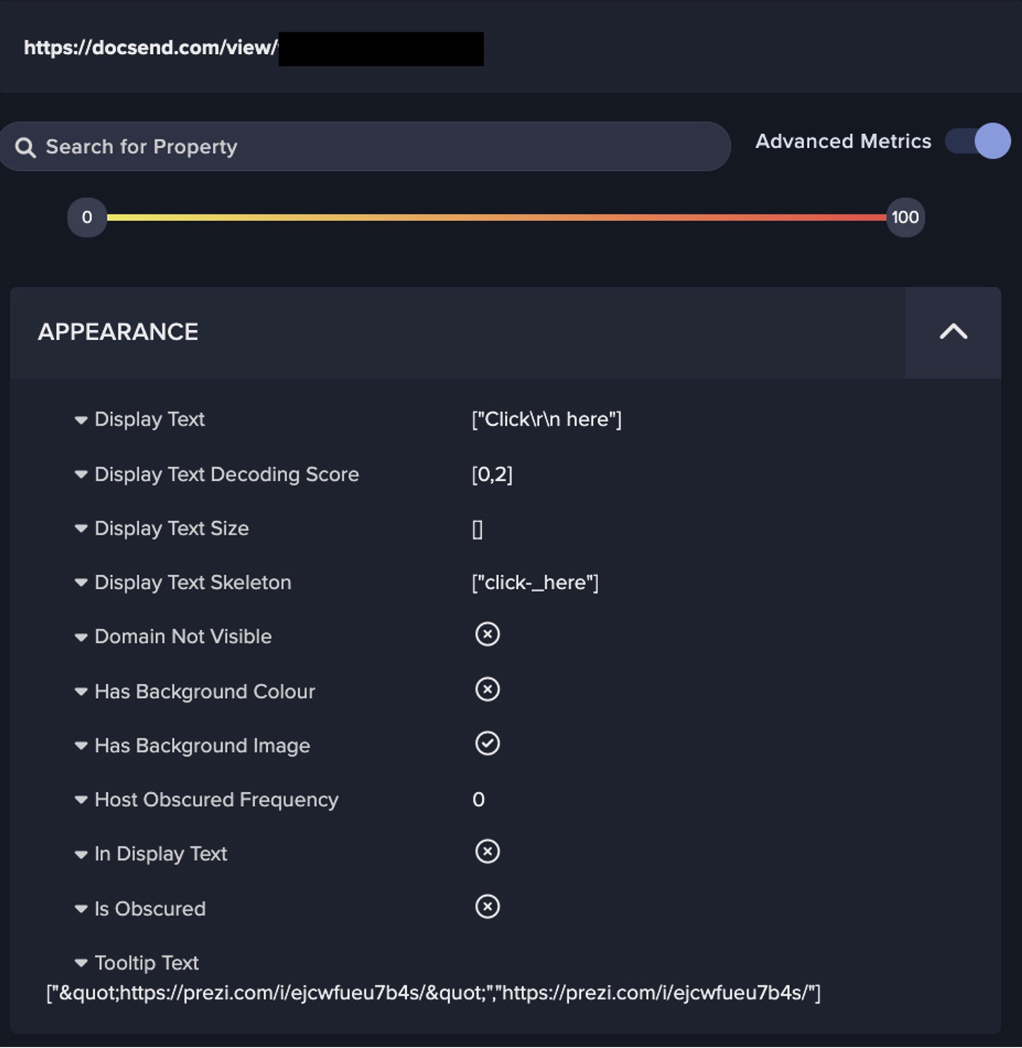

A Raccoon Stealer v2 infection typically starts with a user attempting to download cracked or free software from an SEO-promoted website. Attempting to download software from one of these cracked/free software websites redirects the user’s browser (typically via several .xyz or .cfd endpoints) to a page providing download instructions. In May, June, and July, many of the patterns of download behavior observed by Darktrace’s SOC matched the pattern of behavior observed in a cracked software campaign reported by Avast in June [8].

Following the instructions on the download instruction page causes the user’s device to download a password-protected RAR file from a file storage service such as ‘cdn.discordapp[.]com’, ‘mediafire[.]com’, ‘mega[.]nz’, or ‘bitbucket[.]org’. Opening the downloaded file causes the user’s device to execute Raccoon Stealer v2.

Once Raccoon Stealer v2 is running on a device, it will make an HTTP POST request with the target URI ‘/’ and an unusual user-agent string (such as ‘record’, ‘mozzzzzzzzzzz’, or ‘TakeMyPainBack’) to a C2 server. This POST request consists of three strings: a machine GUID, a username, and a 128-bit RC4 key [9]. The posted data has the following form:

machineId=X | Y & configId=Z (where X is a machine GUID, Y is a username and Z is a 128-bit RC4 key)

The C2 server responds to the info-stealer’s HTTP POST request with custom-formatted configuration details. These configuration details consist of fields which tell the info-stealer what files to download, what data to steal, and what target URI to use in its subsequent exfiltration POST requests. Below is a list of the fields Darktrace has observed in the configuration details retrieved by Raccoon Stealer v2 samples:

- a ‘libs_mozglue’ field, which specifies a download address for a Firefox library named ‘mozglue.dll’

- a ‘libs_nss3’ field, which specifies a download address for a Network System Services (NSS) library named ‘nss3.dll’

- a ‘libs_freebl3’ field, which specifies a download address for a Network System Services (NSS) library named ‘freebl3.dll’

- a ‘libs_softokn3’ field, which specifies a download address for a Network System Services (NSS) library named ‘softokn3.dll’

- a ‘libs_nssdbm3’ field, which specifies a download address for a Network System Services (NSS) library named ‘nssdbm3.dll’

- a ‘libs_sqlite3’ field, which specifies a download address for a SQLite command-line program named ‘sqlite3.dll’

- a ‘libs_ msvcp140’ field, which specifies a download address for a Visual C++ runtime library named ‘msvcp140.dll’

- a ‘libs_vcruntime140’ field, which specifies a download address for a Visual C++ runtime library named ‘vcruntime140.dll’

- a ‘ldr_1’ field, which specifies the download address for a follow-up payload for the sample to download

- ‘wlts_X’ fields (where X is the name of a crypto-wallet application), which specify data for the sample to obtain from the specified crypto-wallet application

- ‘ews_X’ fields (where X is the name of a crypto-wallet browser extension), which specify data for the sample to obtain from the specified browser extension

- ‘xtntns_X’ fields (where X is the name of a password manager browser extension), which specify data for the sample to obtain from the specified browser extension

- a ‘tlgrm_Telegram’ field, which specifies data for the sample to obtain from the Telegram Desktop application

- a ‘grbr_Desktop’ field, which specifies data within a local ‘Desktop’ folder for the sample to obtain

- a ‘grbr_Documents’ field, which specifies data within a local ‘Documents’ folder for the sample to obtain

- a ‘grbr_Recent’ field, which specifies data within a local ‘Recent’ folder for the sample to obtain

- a ‘grbr_Downloads’ field, which specifies data within a local ‘Downloads’ folder for the sample to obtain

- a ‘sstmnfo_System Info.txt’ field, which specifies whether the sample should gather and exfiltrate a profile of the infected host

- a ‘scrnsht_Screenshot.jpeg’ field, which specifies whether the sample should take and exfiltrate screenshots of the infected host

- a ‘token’ field, which specifies a 32-length string of hexadecimal digits for the sample to use as the target URI of its HTTP POST requests containing stolen data

After retrieving its configuration data, Raccoon Stealer v2 downloads the library files specified in the ‘libs_’ fields. Unusual user-agent strings (such as ‘record’, ‘qwrqrwrqwrqwr’, and ‘TakeMyPainBack’) are used in the HTTP GET requests for these library files. In all Raccoon Stealer v2 infections seen by Darktrace, the paths of the URLs specified in the ‘libs_’ fields have the following form:

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/X (where X is the name of the targeted DLL file)

Raccoon Stealer v2 uses the DLLs which it downloads to gain access to sensitive data (such as cookies, credit card details, and login details) saved in browsers running on the infected host.

Depending on the data provided in the configuration details, Raccoon Stealer v2 will typically seek to obtain, in addition to sensitive data saved in browsers, the following information:

- Information about the Operating System and applications installed on the infected host

- Data from specified crypto-wallet software

- Data from specified crypto-wallet browser extensions

- Data from specified local folders

- Data from Telegram Desktop

- Data from specified password manager browser extensions

- Screenshots of the infected host

Raccoon Stealer v2 exfiltrates the data which it obtains to its C2 server by making HTTP POST requests with unusual user-agent strings (such as ‘record’, ‘rc2.0/client’, ‘rqwrwqrqwrqw’, and ‘TakeMyPainBack’) and target URIs matching the 32-length string of hexadecimal digits specified in the ‘token’ field of the configuration details. The stolen data exfiltrated by Raccoon Stealer typically includes files named ‘System Info.txt’, ‘---Screenshot.jpeg’, ‘\cookies.txt’, and ‘\passwords.txt’.

If a ‘ldr_1’ field is present in the retrieved configuration details, then Raccoon Stealer will complete its operation by downloading the binary file specified in the ‘ldr_1’ field. In all observed cases, the paths of the URLs specified in the ‘ldr_1’ field end in a sequence of digits, followed by ‘.bin’. The follow-up payload seems to vary between infections, likely due to this additional-payload feature being customizable by Raccoon Stealer affiliates. In many cases, the info-stealer, CryptBot, was delivered as the follow-up payload.

Darktrace Coverage of Raccoon Stealer

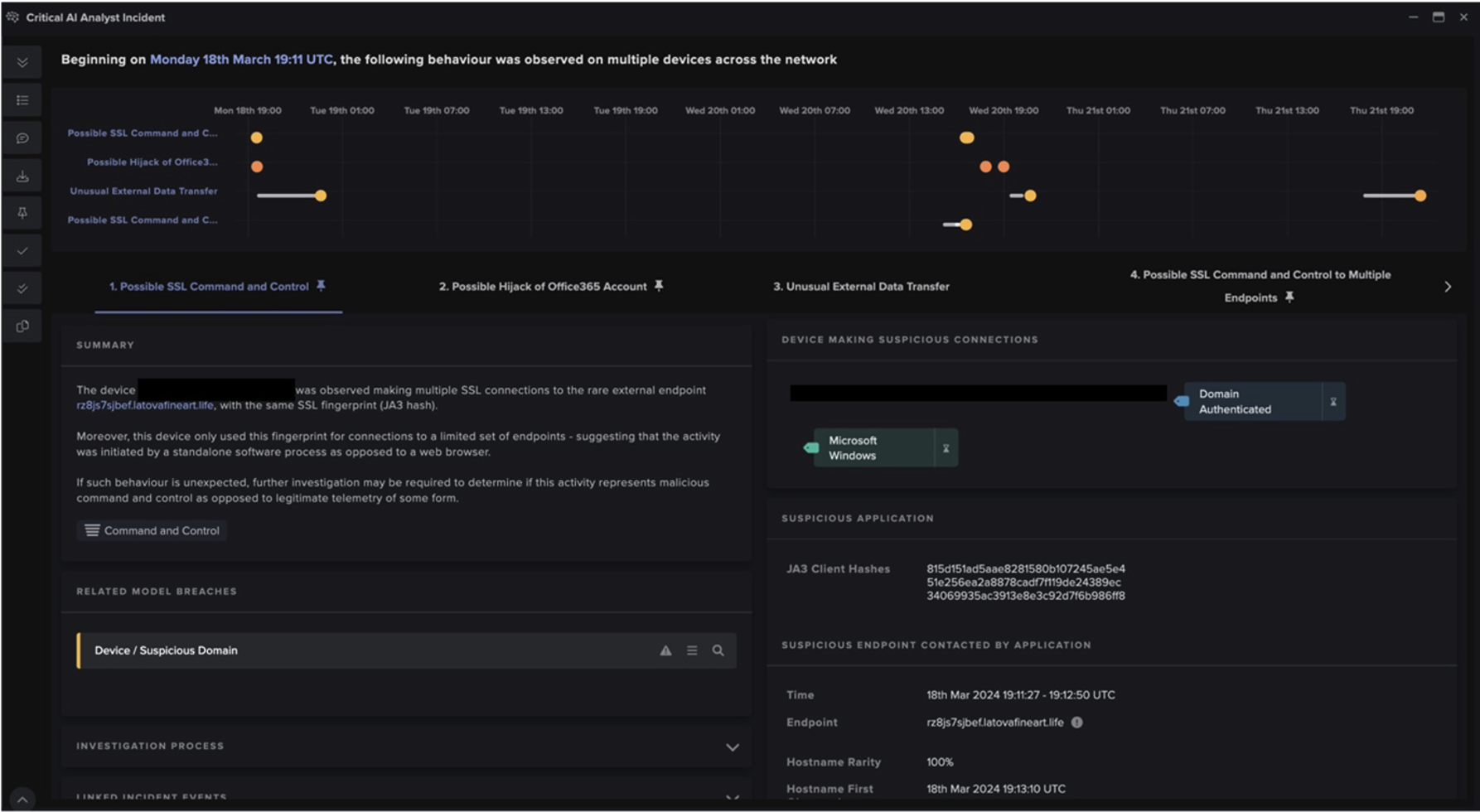

Once a user’s device becomes infected with Raccoon Stealer v2, it will immediately start to communicate over HTTP with a C2 server. The HTTP requests made by the info-stealer have an empty Host header (although Host headers were used by early v2 samples) and highly unusual User Agent headers. When Raccoon Stealer v2 was first observed in May 2022, the user-agent string ‘record’ was used in its HTTP requests. Since then, it appears that the operators of Raccoon Stealer have made several changes to the user-agent strings used by the info-stealer, likely in an attempt to evade signature-based detections. Below is a timeline of the changes to the info-stealer’s user-agent strings, as observed by Darktrace’s SOC:

- 22nd May 2022: Samples seen using the user-agent string ‘record’

- 2nd July 2022: Samples seen using the user-agent string ‘mozzzzzzzzzzz’

- 29th July 2022: Samples seen using the user-agent string ‘rc2.0/client’

- 10th August 2022: Samples seen using the user-agent strings ‘qwrqrwrqwrqwr’ and ‘rqwrwqrqwrqw’

- 16th Sep 2022: Samples seen using the user-agent string ‘TakeMyPainBack’

The presence of these highly unusual user-agent strings within infected devices’ HTTP requests causes the following Darktrace DETECT/Network models to breach:

- Device / New User Agent

- Device / New User Agent and New IP

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Device / Three or More New User Agents

These DETECT models look for devices making HTTP requests with unusual user-agent strings, rather than specific user-agent strings which are known to be malicious. This method of detection enables the models to continually identify Raccoon Stealer v2 HTTP traffic, despite the changes made to the info-stealer’s user-agent strings.

After retrieving configuration details from a C2 server, Raccoon Stealer v2 samples make HTTP GET requests for several DLL libraries. Since these GET requests are directed towards highly unusual IP addresses, the downloads of the DLLs cause the following DETECT models to breach:

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Script from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Multiple EXE from Rare External Locations

Raccoon Stealer v2 samples send data to their C2 server via HTTP POST requests with an absent Host header. Since these POST requests lack a Host header and have a highly unusual destination IP, their occurrence causes the following DETECT model to breach:

- Anomalous Connection / Posting HTTP to IP Without Hostname

Certain Raccoon Stealer v2 samples download (over HTTP) a follow-up payload once they have exfiltrated data. Since the target URIs of the HTTP GET requests made by v2 samples end in a sequence of digits followed by ‘.bin’, the samples’ downloads of follow-up payloads cause the following DETECT model to breach:

- Anomalous File / Numeric File Download

If Darktrace RESPOND/Network is configured within a customer’s environment, then Raccoon Stealer v2 activity should cause the following inhibitive actions to be autonomously taken on infected systems:

- Enforce pattern of life — This action results in a device only being able to make connections which are normal for it to make

- Enforce group pattern of life — This action results in a device only being able to make connections which are normal for it or any of its peers to make

- Block matching connections — This action results in a device being unable to make connections to particular IP/Port pairs

- Block all outgoing traffic — This action results in a device being unable to make any connections

Given that Raccoon Stealer v2 infections move extremely fast, with the time between initial infection and data exfiltration sometimes less than a minute, the availability of Autonomous Response technology such as Darktrace RESPOND is vital for the containment of Raccoon Stealer v2 infections.

Conclusion

Since the release of Raccoon Stealer v2 back in 2022, the info-stealer has relentlessly infected the devices of unsuspecting users. Once the info-stealer infects a user’s device, it retrieves and then exfiltrates sensitive information within a matter of minutes. The distinctive pattern of network behavior displayed by Raccoon Stealer v2 makes the info-stealer easy to spot. However, the changes which the Raccoon Stealer operators make to the User Agent headers of the info-stealer’s HTTP requests make anomaly-based methods key for the detection of the info-stealer’s HTTP traffic. The operators of Raccoon Stealer can easily change the superficial features of their malware’s C2 traffic, however, they cannot easily change the fact that their malware causes highly unusual network behavior. Spotting this behavior, and then autonomously responding to it, is likely the best bet which organizations have at stopping a Raccoon once it gets inside their networks.

Thanks to the Threat Research Team for its contributions to this blog.

References

[2] https://twitter.com/3xp0rtblog/status/1507312171914461188

[3] https://www.esentire.com/blog/esentire-threat-intelligence-malware-analysis-raccoon-stealer-v2-0

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fsz6acw-ZJ

[6] https://riskybiznews.substack.com/p/raccoon-stealer-dev-didnt-die-in

[7] https://medium.com/s2wblog/raccoon-stealer-is-back-with-a-new-version-5f436e04b20d

[8] https://blog.avast.com/fakecrack-campaign

[9] https://blog.sekoia.io/raccoon-stealer-v2-part-2-in-depth-analysis/

Appendices

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Resource Development

• T1588.001 — Obtain Capabilities: Malware

• T1608.001 — Stage Capabilities: Upload Malware

• T1608.005 — Stage Capabilities: Link Target

• T1608.006 — Stage Capabilities: SEO Poisoning

Execution

• T1204.002 — User Execution: Malicious File

Credential Access

• T1555.003 — Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers

• T1555.005 — Credentials from Password Stores: Password Managers

• T1552.001 — Unsecured Credentials: Credentials In Files

Command and Control

• T1071.001 — Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols

• T1105 — Ingress Tool Transfer

IOCS

Type

IOC

Descrizione

User-Agent String

record

String used in User Agent header of Raccoon Stealer v2’s HTTP requests

User-Agent String

mozzzzzzzzzzz

String used inUser Agent header of Raccoon Stealer v2’s HTTP requests

User-Agent String

rc2.0/client

String used in User Agent header of Raccoon Stealer v2’s HTTP requests

User-Agent String

qwrqrwrqwrqwr

String used in User Agent header of Raccoon Stealer v2’s HTTP requests

User-Agent String

rqwrwqrqwrqw

String used in User Agent header of Raccoon Stealer v2’s HTTP requests

User-Agent String

TakeMyPainBack

String used in User Agent header of Raccoon Stealer v2’s HTTP requests

Domain Name

brain-lover[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

polar-gift[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

cool-story[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

fall2sleep[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

broke-bridge[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

use-freedom[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

just-trust[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

soft-viper[.]site

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

tech-lover[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

heal-brain[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

Domain Name

love-light[.]xyz

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

104.21.80[.]14

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

107.152.46[.]84

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

135.181.147[.]255

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

135.181.168[.]157

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

138.197.179[.]146

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

141.98.169[.]33

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.19.170[.]100

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.19.170[.]175

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.19.170[.]98

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.19.173[.]33

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.19.173[.]72

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.19.247[.]175

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.19.247[.]177

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

146.70.125[.]95

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

152.89.196[.]234

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

165.225.120[.]25

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

168.100.10[.]238

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

168.100.11[.]23

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

168.100.9[.]234

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

170.75.168[.]118

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

172.67.173[.]14

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

172.86.75[.]189

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

172.86.75[.]33

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

174.138.15[.]216

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

176.124.216[.]15

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.106.92[.]14

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.173.34[.]161

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.173.34[.]161

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.225.17[.]198

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.225.19[.]190

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.225.19[.]229

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.53.46[.]103

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.53.46[.]76

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

185.53.46[.]77

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

188.119.112[.]230

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

190.117.75[.]91

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.106.191[.]182

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.149.129[.]135

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.149.129[.]144

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.149.180[.]210

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.149.185[.]192

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.233.193[.]50

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]138

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]17

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]192

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]213

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]214

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]215

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]26

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.43.146[.]45

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

193.56.146[.]177

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

194.180.174[.]180

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

195.201.148[.]250

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

206.166.251[.]156

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

206.188.196[.]200

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

206.53.53[.]18

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

207.154.195[.]173

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

213.252.244[.]2

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

38.135.122[.]210

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.10.20[.]248

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.11.19[.]99

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.133.216[.]110

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.133.216[.]145

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.133.216[.]148

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.133.216[.]249

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.133.216[.]71

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.140.146[.]169

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.140.147[.]245

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.142.212[.]100

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.142.213[.]24

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.142.215[.]91

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.142.215[.]91

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.142.215[.]92

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.144.29[.]18

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.144.29[.]243

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.15.156[.]11

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.15.156[.]2

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.15.156[.]31

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.15.156[.]31

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.150.67[.]156

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.153.230[.]183

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.153.230[.]228

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.159.251[.]163

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.159.251[.]164

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.61.136[.]67

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.61.138[.]162

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.67.228[.]8

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.67.231[.]202

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.67.34[.]152

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.67.34[.]234

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.8.144[.]187

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.8.144[.]54

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.8.144[.]55

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.8.145[.]174

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.8.145[.]83

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.8.147[.]39

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.8.147[.]79

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.84.0.152

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.86.86[.]78

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.54[.]110

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.54[.]110

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.54[.]95

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.55[.]115

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.55[.]117

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.55[.]193

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.55[.]198

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.55[.]20

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.89.55[.]84

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

45.92.156[.]150

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.36[.]154

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.36[.]230

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.36[.]231

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.36[.]232

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.36[.]233

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.39[.]34

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.39[.]74

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.39[.]75

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.182.39[.]77

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.118[.]33

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.176[.]62

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.177[.]217

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.177[.]234

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.177[.]43

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.177[.]47

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.177[.]92

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.177[.]98

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.22[.]142

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.23[.]100

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.23[.]25

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

5.252.23[.]76

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

51.195.166[.]175

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

51.195.166[.]176

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

51.195.166[.]194

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

51.81.143[.]169

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

62.113.255[.]110

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

65.109.3[.]107

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

74.119.192[.]56

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

74.119.192[.]73

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.232.39[.]101

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.73.133[.]0

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.73.133[.]4

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.73.134[.]45

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.75.230[.]25

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.75.230[.]39

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.75.230[.]70

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.75.230[.]93

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.100[.]101

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.102[.]12

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.102[.]230

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.102[.]44

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.102[.]57

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.102[.]84

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.103[.]31

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.73[.]154

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.73[.]213

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.73[.]32

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

77.91.74[.]67

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

78.159.103[.]195

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

78.159.103[.]196

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

80.66.87[.]23

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

80.66.87[.]28

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

80.71.157[.]112

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

80.71.157[.]138

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

80.92.204[.]202

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

87.121.52[.]10

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

88.119.175[.]187

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

89.185.85[.]53

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

89.208.107[.]42

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

89.39.106[.]78

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

91.234.254[.]126

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.104[.]16

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.104[.]17

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.104[.]18

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.106[.]116

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.106[.]224

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.107[.]132

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.107[.]138

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.96[.]109

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.97[.]129

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.97[.]53

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.97[.]56

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.97[.]57

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.131.98[.]5

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.158.244[.]114

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.158.244[.]119

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.158.244[.]21

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.158.247[.]24

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.158.247[.]26

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.158.247[.]30

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

94.158.247[.]44

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

95.216.109[.]16

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

IP Address

95.217.124[.]179

Raccoon Stealer v2 C2 infrastructure

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/mozglue.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/nss3.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/freebl3.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/softokn3.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/nssdbm3.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/sqlite3.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/msvcp140.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/aN7jD0qO6kT5bK5bQ4eR8fE1xP7hL2vK/vcruntime140.dll

URI used in download of library file

URI

/C9S2G1K6I3G8T3X7/56296373798691245143.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/O6K3E4G6N9S8S1/91787438215733789009.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/Z2J8J3N2S2Z6X2V3S0B5/45637662345462341.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/rgd4rgrtrje62iuty/19658963328526236.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/sd325dt25ddgd523/81852849956384.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/B0L1N2H4R1N5I5S6/40055385413647326168.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/F5Q8W3O3O8I2A4A4B8S8/31427748106757922101.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/36141266339446703039.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/wH0nP0qH9eJ6aA9zH1mN/1.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/K2X2R1K4C6Z3G8L0R1H0/68515718711529966786.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/C3J7N6F6X3P8I0I0M/17819203282122080878.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/W9H1B8P3F2J2H2K7U1Y7G5N4C0Z4B/18027641.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/P2T9T1Q6P7Y5J3D2T0N0O8V/73239348388512240560937.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/W5H6O5P0E4Y6P8O1B9D9G0P9Y9G4/671837571800893555497.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/U8P2N0T5R0F7G2J0/898040207002934180145349.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/AXEXNKPSBCKSLMPNOMNRLUEPR/3145102300913020.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/wK6nO2iM9lE7pN7e/7788926473349244.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload

URI

/U4N9B5X5F5K2A0L4L4T5/84897964387342609301.bin

URI used in download of follow-up payload